Director Eugene Afineyevsky: "It is important not to let the world get used to the war in Ukraine as we got used to the war in Syria

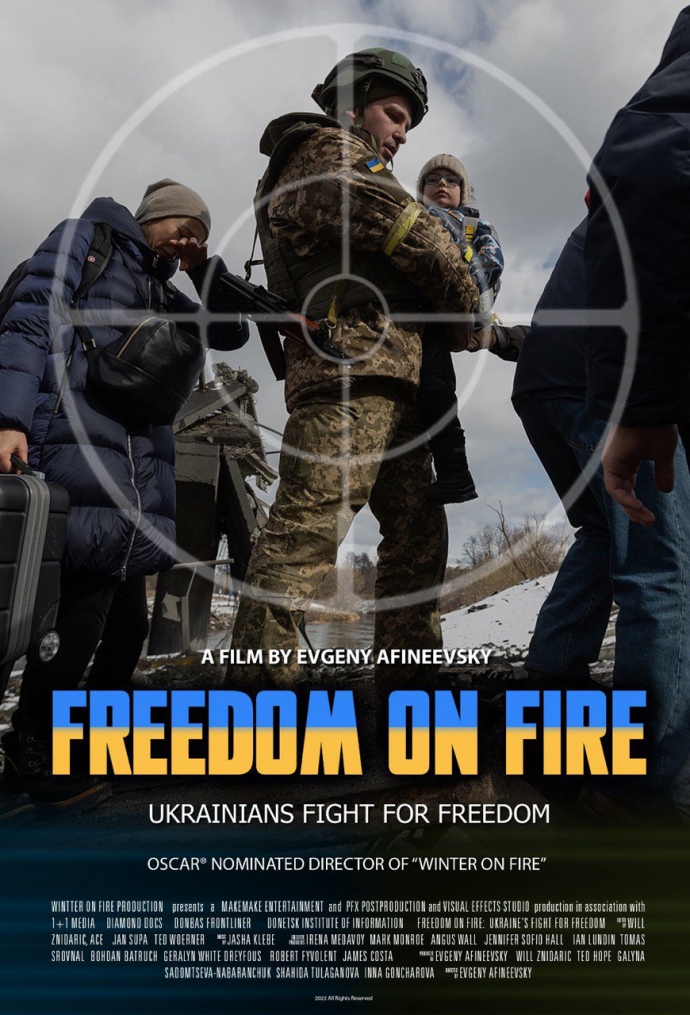

American director Yevhen Afineyevsky made his first documentary about Ukraine during the 2013-2014 Revolution of Dignity. His work Winter on fire: Ukraine's struggle for freedom was nominated for an Oscar and an Emmy.

In 2014, Netflix bought the rights to the film. According to the filmmaker, he invested most of the proceeds from the sale of the rights to promote the film, making "Winter on fire" available to millions of subscribers around the world. "I wanted to explain to the world the phenomenon of the Ukrainian revolution," director Afineyevsky explains his motivation.

On the night Russian missiles flew on Ukrainian cities, Yevgeny was already planning how he would document the war in Ukraine. Within five months of the war, he managed to assemble a team of 43 cameramen and 9 editing directors. Dozens of people participated in the shooting of the film, more than a hundred people were interviewed. In five months, Evgeny Afineevsky put together the puzzle of eight years of Ukrainian war.

Freedom on fire: Ukraine's fight for freedom" was premiered in early September at the Venice Film Festival. The film has already been shown at a number of festivals. And now there are plans to promote it.

"Ukrainska Pravda" talked to the director about why it is important not to let the world forget about Ukraine.

- How did the war start for you? And what motivated you to come to Ukraine?

- The war started for both Ukrainians and me in 2014, but the whole world did not feel it. The whole world saw the moment of the annexation of Crimea and the occupation of the Donetsk region, but it abstracted from that pretty quickly. And if at the very beginning of 2014 we could still consider it a local war, then look how quickly today it has turned into World War III. It is precisely because the rest of the world pretended that it was not concerned by this war. It was this realization that forced me to work in crazy mode, to throw everything I had into making this documentary project.

- For people who live their own lives around the world, the war in Ukraine is a backdrop for them. This is what these people should know about our situation. How should they feel when they watch this film?

- By archiving the war, I don't show what the world audience sees on the news: trenches, soldiers, advances, defeats, massive graves. I showed ordinary people. I told the stories of mothers and children about how they live when there is a war in their country. I create this bridge here between humanity, which lives a quiet life, and people who fight with their heads held high and with a smile for the future of their country.

This is how I plunge my audience into the life of ordinary Ukrainians. Life where every night a mother, putting her child to bed, prays that they will wake up tomorrow. The kind of life that is unfamiliar to another mother who goes to bed every day looking at her child with a smile on her face and wakes up in the morning without anxiety about the future. I put these things together. I've combined stories of medics, where people are fighting for life with nothing in their hands, with stories of medics who have everything in our hospitals, and can't imagine what it's like to work in front-line conditions, to fight for life.

So it will be easy for the audience, first, to "connect" with my heroes, and second, as I said, to dive into that world, where I and our cameramen have been personally.

Like any other person, I cry just as much when I watch my film. And I feel the same way about my characters. And I'm sure these feelings are not alien to people, they allow them to remain human beings capable of empathy.

- Do you have a permanent team in Ukraine that you work with or do you recruit a team for each project?

- I have a permanent team for post-production with whom I've made all my films, I work with them all the time. And not only on Ukrainian subjects. In Ukraine there is a very good level of specialists in film industry. And since I make my own films according to my own motives and values, that is without the support of any film studio, all my films are independent, they are A&A: activism, activism and action. And for me, as an independent director and film producer, value for money is always important. I find this ratio almost ideal in the Ukrainian industry.

- How did you manage to work with 43 cameramen and why were you in such a hurry to release the film as soon as possible, because the war was not over yet?

- From the beginning I knew that the media cycle of interest in Ukraine would end just as quickly as in Syria. First everyone was interested in the war in Syria, and then even the use of chemical weapons against civilians did not arouse interest. I have my own special story with Syria.

I got to know Syrian doctors back on the Maidan. I became very interested. And when the Maidan ended, I flew to Syria to film. I wanted to tell the story of that country. In Syria, I saw the very Russian army that supports Assad's dictatorship and destroys Syrian civilians. I saw cities destroyed by carpet bombing and millions of refugees. At the same time, I heard all this polemic in Europe about Syrian refugees taking over European cities. And they were just saving their children from being killed. Now there are stories about Syria, which has been at war for over 10 years, twice a year.

I was afraid that the interest to Ukraine would also decrease within six months. So in February I already understood that we needed a film. Because when the heat comes down, people will get tired of thinking about Ukraine, of helping Ukrainians.

- One of the main characters in your film is Natalia Nagornaya, a war correspondent for 1+1; did you know her before the war?

- When I saw how journalists and photographers were being killed and hunted mercilessly in February and March, I already knew that my main character would be a journalist. Natasha and I had known each other since Maidan 2014. Natasha had been working with the war theme for all of these eight years. And she, of course, has grown a lot over the years. War makes people stronger, tougher. Natasha Nagornaya embodies for me the image of a journalist who serves his country on a par with the military, protects his society, fulfills his duty. I wanted to show in the film exactly the young people whose characters were formed in this war.

- Who else of your heroes do you consider in some sense a role model?

- Natasha Nagornaya introduced me to Stas Stovban. For me, Stas became a bright embodiment of those young people from Ukraine who went to war at the age of 20. He was at Donetsk airport together with Igor Bronevitsky, whom the whole Ukraine knows. In front of Stas' eyes, Igor was shot by Motorola. He was a prisoner of war and lost a leg.

Stas Stovban is a man who lived together with his country through the most difficult and most important stage of history. And returning on one leg from captivity, he almost immediately went into the paratroopers to fight for his country. And he was one of the first to liberate Bucha. That's how I see the Ukrainian youth today. I wanted such heroes to talk about war in my film.

You have the character Anya in your film, whose husband joined the Azov battalion just before the aggression began.

- He was in the landing force when their son Svyat was born. He decided to change his life in order to help Anna bring up her child, and he went to work at Azovstal. And then, when the attack on Mariupol began, he joined the "Azov" battalion. Anya and her baby spent two months in a bomb shelter under Azovstal. And this, of course, is also a role model now for Ukraine, when women have to save children, to survive in inhumane conditions, and men have to fight to save the country. I adore Anya, who is now doing her best to get the children out of captivity, to reach the hearts and minds of the world community. And she is doing her best, doing her utmost to get the boys out of there.

- What did the making of this documentary teach you?

- You have to be inside the situation and, on the other hand, on the outside. To be able to tell a story in a detached way. Really, I learned that when I was working on the film Winter on fire. When I took the first version of the montage in the beginning, it was incomprehensible to a lot of Hollywood filmmakers.

Americans didn't understand why people were getting beaten up and then they went back out on the streets. And we had to go deeper and show why the Ukrainian people were ready to fight to the last drop of blood for their country in 2013-2014. What the idea of democracy, freedom of speech, human rights mean to Ukrainians, and how they see their future. And that's when I learned how to tell any story from scratch. That's why we made an animated intro at the beginning of Freedom on fire, which we worked on with professional historians. Precisely in order to give the necessary historical context, it would explain to the viewer that Putin didn't decide to destroy the Ukrainian people on February 24, 2022, but that this historical cycle has been going on for centuries. You know what I'm proud of? Winter on fire, the captured history of the Ukrainian Maidan was, in a sense, a manual of "revolution for beginners." We showed the world how people can stand up against a dictatorship. I know that for activists from Venezuela, Nicaragua, Lebanon, Hong Kong - the Ukrainian experience was a "manual" that encouraged them. And I also hope that the Ukrainian experience of fighting for their future will inspire other people who are now currently under occupation.

Your film Winter on Fire, the first about Ukraine, was sold to Netflix. How do you plan to promote the Freedom on fire?

- In the first case, it was important for me to return everything that my team and I spent on shooting and for Netflix to invest in the promotion of our project. For me, the Maidan documentary was not a story about making money, but about justice, about giving a voice to Ukrainians. This film really separated Ukraine from Russia. I have been living abroad since '91, and I can definitely say that few people distinguished between these countries before the release of Winter on Fire.

Now I also have the same goal - to bring Freedom on fire to the world, to make it possible for the whole world to see this war.

Anastasiya Ringis