"You should all be raped for more Russians to be born," the guards said. Svitlana Vorova from Azov Regiment talks about 11 months of captivity

In February 2015, 28-year-old Azov Regiment fighter Oleksandr Kutuzakiy, call sign Kutuz, and his comrade went on another raid near Shyrokyne east of Mariupol. They were supposed to deliver ammunition to the front line and take the wounded.

A vehicle with Ukrainian soldiers was ambushed and shot. The bodies of the soldiers, who were kept by Kadyrovites for some time, were returned mutilated. At his mother's request, Kutuz was buried in an open coffin so that people could see the atrocities of the occupiers. Oleksandr received the Ukrainian Order "For Courage" of the III degree posthumously.

15-year-old Yakiv Kutuzakiy was deeply affected by the loss of his older brother. So when he learned in 2020 that his mother, Svitlana Vorova, was going to join the army, he almost had a hysterical fit. However, the woman strongly decided that she had to continue her older son's work and joined Azov.

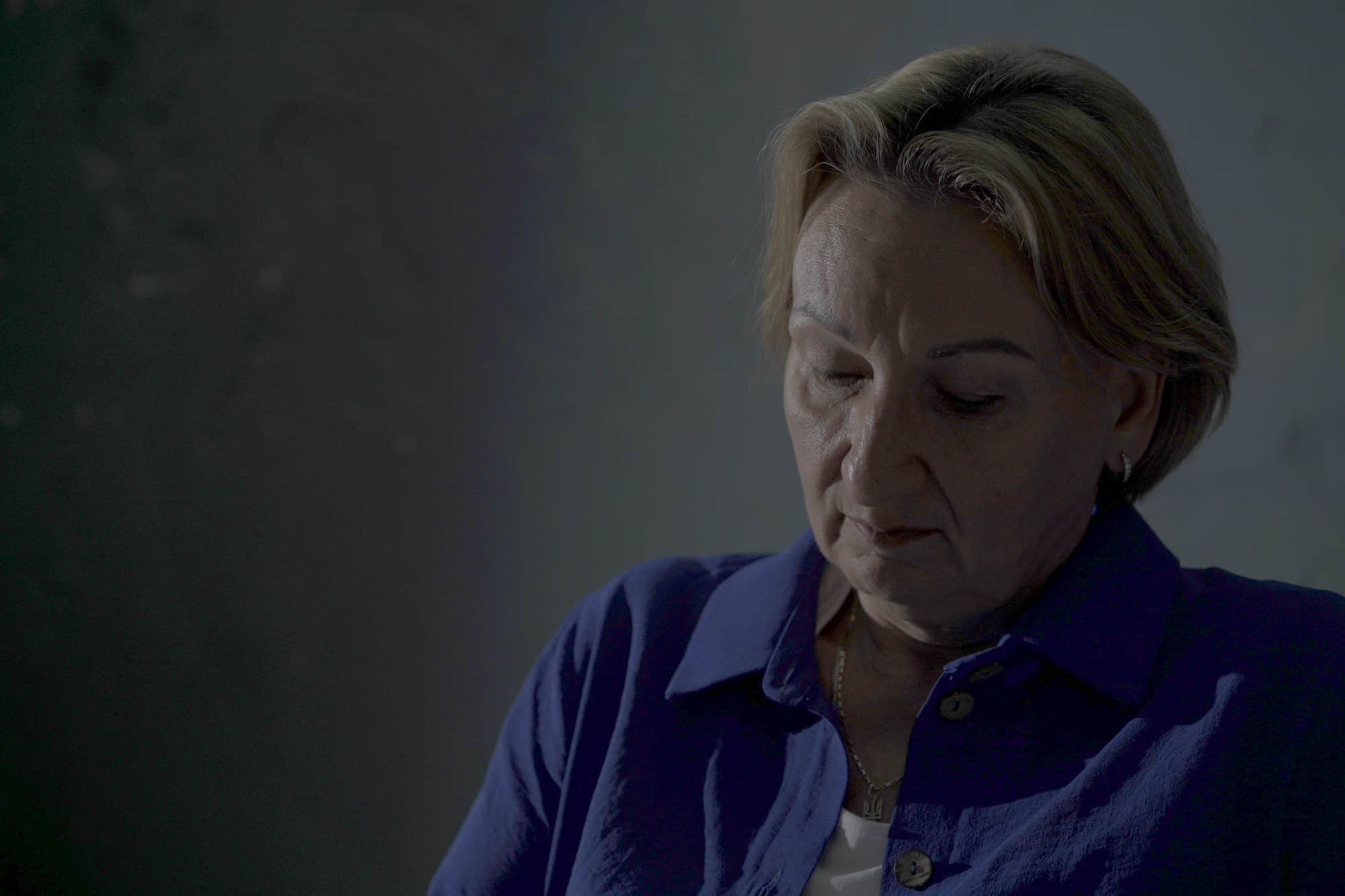

We meet in Kyiv, in the lobby of the clinic where Svitlana is undergoing rehabilitation after spending 11 months in captivity. She's wearing a formal pantsuit, her wavy hair is tied up in a neat hairstyle. The 55-year-old woman's gaze remains calm and focused, even when she smiles. From behind the lapel of her jacket, a tattoo fragment can be seen.

"While still in captivity, I promised that when I was released, I would get a tattoo with a viburnum. And a map of Ukraine," Svitlana unbuttoned the top button of her shirt. "And here it says 'unbreakable,' but I'll also add 'made of steel' and 'free'."

Before joining the military, Odesa resident Svitlana Vorova worked as a technical department engineer at Ukrzaliznytsia, the state railways operator. In Azov, she became a clerk in the supply service. She had to move from Odesa to the city of the unit's deployment, Urzuf, a town halfway between Mariupol and Berdyansk.

This was the place where Svitlana met February 24, 2022.

"On an emergency call, we went to Mariupol, to Azovstal steel mill. The whole Azov Regiment was sent there," Svitlana says. "We stayed there for 86 days, until the day we were captured. There were at least 150 people in one bunker."

"After the bunkers with the kitchen were blown up, we didn't receive any more provision. I and the other girls organized ourselves and started cooking and cleaning up the garbage. We did everything to ensure that the guys fulfilled their combat missions and didn't worry about everyday issues. We baked bread, cooked meals, and cleaned everything up. We took out the waste."

"We were bombed a lot. From ships, from tanks, from the air. There were moments when I even wrote messages to my children, saying goodbye to them. Many bunkers were bombed. Many soldiers, my friends, were killed. Some were burned alive."

Leaving Azovstal, interrogations, explosion in Olenivka

– How did you find out that you would have to surrender?

– Commander told us. He talked to the commander-in-chief and received an order [to surrender] to save the regiment. The part of the regiment that still remained there.

– How did you react to this order?

– On the one hand, there was joy: I survived. On the other hand, I didn't know what to expect. We realized that we would be tortured. We were prepared for the worst, but we hoped that Russia would fulfill the requirements of the Geneva Convention.ї.

The soldiers started leaving Azovstal on May 17, people came out bunker by bunker, in separate columns.

Our bunker was the last one to leave, on May 20. First in groups of five people, then of ten. We were searched, stripped of our personal belongings and escorted to the buses.

These buses brought us to Olenivka prison. There, all the girls were placed in a detention center. It was a disciplinary isolator, a six-bed cell, where there were 25 of us, sometimes more, up to 30. Two girls slept on each of the six bunks. The rest of us slept on the floor. Like sprats, one next to the other.

A toilet was right there, in the cell. Everything was completely unsanitary, we had no running water. Through the feeder (a hole in the door) we were given jars of industrial water. We tried to strain or defecate it in order to make it drinkable. Also we tried to do some laundry, to wash ourselves, at least wash our hands, because it was horrible. [Due to the unsanitary conditions] the girls had constant diarrhea, intestinal disorders.

Once a week, at best, we were taken to the shower. And it was a speed play. The prison staff took 5 or 10 people to the shower and gave us all 5-10 minutes. During this time, we had to wash ourselves and do some laundry. Then we hung the wet clothes, of course, in our cell. Olenivka was a nightmare.

– Did you have any communication with the prison officers?

– Not with managerial staff. But regular jailers talked to us. Well, more often they just mocked us, but there also was communication. They kept saying that no one needed us. They insulted us all the time, called us chickens and Azov prostitutes.

– And what did you talk about with each other?

– We discussed everything: recipes and our families. We talked about our dreams. I encouraged the girls to talk about the future. One evening I said: "Girls, let's pray at night." They replied: "Let you, Grace, read the prayer, and we'll repeat after you." So in our cell we had a tradition: from the moment we started and until the day of our exchange, we recited the Lord's Prayer,

– Is Grace (in Ukrainian – Gracia, Грація – UP) your call sign?

– Yes, it is. I was told to choose a call sign when I joined the army. I had several options, but they were already taken. And then I thought, why not Gracе?

– Can you remember the call signs of the others?

– Khana, Dika, Ginger. I also had a friend, Romashka (Ukrainian for "Daisy" – UP), she too was the mother of a fallen soldier. Unfortunately, she also died. She was very fond of flowers, daisies, and that's how she got her call sign.

– What did they feed you?

– In Olenivka? It's hard to say that we were fed. Except for the bread baked by our girls. The head of the prison ordered to create teams of bakers so that the girls would go to the bakery and bake bread. That was the only tasty thing there. Everything else was water with a piece of potato floating in it – how can you call that food? Porridge in which uncleaned fish was cooked, with spines, bones, everything. No oil, no salt, no nothing.

In total, in 11 months of captivity, I lost 30 kilograms.

– Were there any interrogations?

– In Olenivka, there were. As I said, we were put in a disciplinary isolator. Men were in barracks. So those whom the Russians had some suspicions about, that maybe some guy was a sniper, or they didn't like soldier's tattoos – some of them had nationalist tattoos, coats of arms, portraits of [the Ukrainian nationalist Stepan] Bandera – they were sent to the disciplinary isolation unit to us.

Among the jailers, there was a team from "DNR" (so-called Donetsk People's Republic, illegal Russia-backed separatist entity – UP) who were very cruel and abused the guys a lot. Really a lot. They beat them, taped their arms and legs and continued to torture them. They beat them with tasers. We could only hear them screaming and moaning. We heard everything, during the day and in the nighttime.

After one of the interrogations, one guy was taken out on a stretcher, He was dead – the jailers said he had allegedly committed suicide. But we heard how the "DNR" men came to his cell in the middle of the night repeatedly, beating him, throwing him on the ground and abusing him as much as they could.

– Didn't they take women for interrogation?

– They did. But apart from being insulted and pushed, we weren't beaten like that. There was no such thing in Olenivka. The jailers could only hit us on the shins or on the back. As far as I know, there was no sexual harassment either. They only said: "it's needed to rape all of you so that you give birth to Russians for us."

– What were you interrogated about?

– They were looking for snipers, interrogating who was doing what, all things like that. But personally, they were interested in our thoughts, what we think about and how. And what motivates us to fight.

They asked me how I felt about Russians. I said, well, I have a normal attitude. I have a normal attitude towards adequate Russians. And if a person is normal, it doesn't matter what nationality he or she is or where he or she lives. But they (interrogators – UP) don't want to realize that they have come to another country.

– How did you get through the explosion in Olenivka?

– They (the jailers – UP) were walking around very cheerfully before the explosion. And then it happened. There was panic. Or rather, an imitation of panic, I could feel it. It was clear from their behavior that it wasn't ours [who did this], you know? And we could hear where the missiles were coming from. We heard the guys moaning and screaming.

– How do you explain to yourself why they did this?

– To break us. They tried to assure us that it was the Ukrainian army who did this.

We did not fall for it. Because, as I said, we could hear very well where the missiles were coming from.

It's hard to believe that Ukrainians would shell [Azov soldiers]. Why would they do that?

Punishment cell, mouse hunting, torture by Gazmanov, blue and yellow threads on the radiator

– What helped you withstand captivity?

– You know, it was better in the beginning, as there were a lot of us in the cell. Although it was challenging, because all the time there were questions: "when will you be exchanged?", "why haven't you been exchanged yet?", "what is happening in Ukraine?".

In Olenivka we could hear a little bit what the jailers were telling each other. We also watched their moods. When they are in a bad mood, that's probably when ours hit [Russians] badly. And when they are in a good mood, ours probably suffer.

But when we were transferred to Russia on September 27, there was a complete information vacuum. At first, there were three of us in each cell, and since January – only two. It's hard to be with one person 24/7. We've already discussed everything: books, all the affairs, hobbies, everything. It's hard morally [to stay together].

We were looking through the window, and when the sky was clear, the sun was setting, we saw a blue sky and an orange-yellow sunset. What do you think we saw? Of course, our flag. We said: look at the sunset. This is Ukraine! Everything will be fine.

By order of the head of the detention center, sometimes we were shown Soviet films. They were good movies. "The Gas Station Queen", "Wedding in Malynivka", in these films everyone wears [traditional Ukrainian] embroidered shirts, you know? Or "Only Old Men Go to Battle". [Character played by actor Leonid] Bykov says: "You were flying over my Ukraine, where the sky is bluer and the grass is greener."

This gave us strength. Maybe the Russians didn't understand this. The head of the detention center allowed us to read books. Of course, all of them were in Russian. We weren't allowed to speak Ukrainian at all. And also we couldn't speak out loud, only in a whisper. But we read. We read a hundred books in seven months.

When I wasn't reading, I washed the walls. While I was in Russia, I've changed five cells. I washed all the walls, all the floors, all the toilets in those cells. The authorities constantly demanded to clean.

– Were you in a punishment cell?

– Well, in Olenivka I was in the so-called punishment cell. It was just a typical cell with worsened conditions: 10 people were kept in a room 2.5 by 2.5 meter. And while in a regular cell we were taken out to the yard to walk and breathe [fresh air] once a week, in the punishment cell we were taken out once every three weeks, and sometimes once a month.

The only small window was covered with tin, in which holes in a Z-shape were drilled. Inside there was a bunk bed. Two people slept on each bunk, and the rest slept on the floor, under the bunk, on the toilet railing, on the table, on the bench. I slept under the bunk.

The floor was cement. We asked for mattresses, and sometimes jailers gave them to us. Although you can't call it a mattress – it was a cloth with cotton wool, dirty and moldy. Mice ran on us. We used to catch these mice, it was our entertainment.

The punishment cell in the pre-trial detention center in Russia was different. It was a cell for one person, 1.5 by 3 meters with a small window under the ceiling, which you couldn't approach. And it was also fenced with a grate, from which the wind blew strongly.

It was the beginning of February, with snow and rain, and a single-pane window with cracks in it. It was very cold, and we shivered both day and night. This made it impossible to sleep, and in the morning we were forced to get up and take the mattress to a separate room. The bench was raised and locked by the guards so that we could not sit.

In addition to the cell, there was a toilet, a sink, and a small table with a chair. But you are not allowed to sit at all. That is, you sit while the guard is not around. As soon as he or she comes, you have to stand by the door and say greetings. And then you have to fulfill his or her whims: sing the Russian anthem, sing Russian songs, squat, wash the floor. We must have washed the floor ten times a day, if not more. It was such a torture.

The Russians started cutting one girl's hair – she had quite long one – just because she was looking towards the door, towards the keyhole. But the hair clipper broke down. It was probably her luck that they didn't shave her completely.

– You were forbidden to look at the door?

– No. You can't talk out loud, you can't look at the door. Even when they come, you can't look [there]. You cannot go to the window and look out into the yard.

– Why were you kept in the punishment cell? Was it a punishment?

– Yes, it was. In Olenivka, it was because I didn't answer the head of the prison the way he expected. He really wanted us to give an interview [to Russian propagandists], but I told him that my family doesn't watch Russian television. He didn't like that, and ordered me to be taken to the sixth cell of the disciplinary isolator. I spent a month and a half there.

Another girl was put in the punishment cell because she asked the jailman if we would really be given compote from the cherries that grew on the territory of the colony. Nava, Ptashka (famous Ukrainian female soldiers – UP) and other girls were in this punishment cell too.

And in Russia, I and Olena, a girl who was in a regular cell with me, were put to punishment cells for hanging threads on the radiator. Two little threads, blue and yellow. It was just a coincidence: we pulled them out of the towels we were given to wash the floor at different times. We used to hang those strings on the radiator to mark the day of the week. A few months later jailers found these threads. They said we were embroidering the flag of Ukraine, and that was it: Russians transferred us to the punishment cell for a week.

– You say they forced you to squat?

– Yes. Fifty times at least, one thousand at most.

– And they counted that?

– Yes. They ordered us to count out loud. So loud that they could hear. The girls did twenty to fifty push-ups. They made us learn the Russian anthem and sing it repeatedly. There were days when we sang it ten times. They turned on radio with Russian songs and then forced us to sing them. [Songs by Oleg] Gazmanov, [Nadezhda] Babkina, which I just hate after that. It's a torture. This is psychological and moral abuse of people.

– All this time you had no contact with your family. So you had no idea what was happening in Ukraine?

– Sometimes we were taken for interrogation by investigators. And they listed the cities that [the Russians] allegedly captured. They said that Odesa would be taken soon. But we had no confirmation of this. And we couldn't tell them anything because we didn't know what was going on.

At the time we were taken prisoner, the city was being bombed very heavily - I was riding in a bus and saw the destroyed Mariupol. I was in tears.

The exchange, the first tiramisu in freedom, dreams about shelling

– We were waiting for the exchange every day, but we didn't know when it would happen until the last moment. Even when the jailers raised us up and started calling us out of the cell by name, we didn't know why.

It was in the middle of the night. They call your name, you go out, and your neighbor stays in – how come? I say: "Lenochka, if anything, we'll hold on [together]". We studied the phones of our relatives. In case I go out [first], I have to call her family and tell them that everything is fine. So should she.

And then the administration gave us our things and told us not to take anything else. So you don't understand what's going on: you're being taken somewhere, and no one tells you where. Although there were some jailers who whispered that we were going for an exchange.

It was a complete surprise, but we were waiting for it every second. So as soon as it happened, it seemed like a dream. Even when we arrived at the state border, when we had already been exchanged, transferred to other buses, and Ukrainian military officer came in and said: "Ukraine welcomes you." You just look at him and don't understand whether it's true or maybe it's the Russians in disguise and mocking us like that.

– What were your first days in Ukraine like?

– My children came to me immediately. When I saw them, it was the biggest joy possible. They were crying, saying: "Mom, you're so small now". I said: "Yes, but I'm alive and well, everything is fine, it will grow."

– In captivity, you were deprived of almost everything. What was the first thing you did to please yourself when you became free?

– You know, when we were in captivity, Lena and I were always dreaming – we happen to have the same tastes – of a sweet curd dessert. My favorite one is tiramisu. Of course, I told the girls (compatriots – UP) that. And when we were in the hospital, the first thing the girls brought was a dessert cake, tiramisu.

– Do you have night dreams?

– Yes, I do. Shelling, bombing. I still feel anxious. When the thunder is loud, I can't sleep. It's like I hear explosions. And I can't ride the subway alone anymore. Because the sound of a train approaching is like a fighter jet flying for me.

– You are currently undergoing rehabilitation. What's next for you?

– To serve [in the Ukrainian army]. To continue my work. I will serve until I am expelled (smiles).

And my children? They know that their mother is an independent woman, and everything will be like she said.

Yevhen Safonov, for Ukrainska Pravda

This article was created as part of the Life in War project with the support of the Public Interest Journalism Laboratory and the Institute for Human Sciences (Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen).