Abandoned Transnistria

In the southwest Ukraine borders with an unrecognized territory – Transnistria or PMR (Prednistrovian Moldavian Republic), a self-proclaimed republic, that broke away from Moldova in 1990. Since then, Transnistria has been unsuccessfully waiting for recognition from Russia and joining the Russian Federation. But instead the unrecognized republic has received Russian subsidies, Russian propaganda and Russian flags on the streets.

"Russian Spring" patriots

An elderly man in a dark brown suit lowers the "PMR" flag in front of the Bender city administration. Then he puts up "The Undeclared War" posters on the lawn nearby – a chronicle of events in Transnistria in 1992.

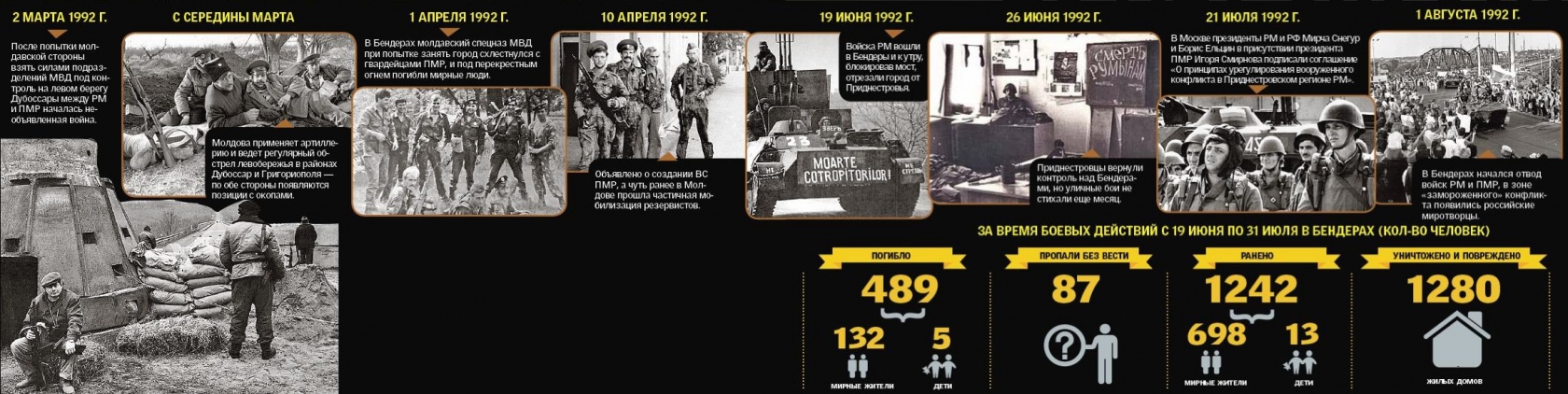

Every June since that year the city had been honouring those who died during the "Battle of Bender" – one of the key confrontations in the conflict between self-proclaimed Transnistria and armed forces of Moldova.

The region broke away from Moldova at the beginning of 90-ies as a result of Unionist movement, that saw Moldova and Romania unified.

In 1992, as a result of the war that had lasted for 6 months, about a thousand people got killed, including civilians, several thousand wounded and around 100 thousand people became refugees.

When you enter Bendery, the only city in Transnistria situated on the right bank of Dniester, you pass by a military checkpoint, like those you can see now in conflict zone in Donbass, with armed soldiers, trenches and hidden armed vehicle. The Russian flag over the checkpoint indicates Russian "peacekeeping troops" dislocated in the area.

The checkpoint is situated nearby two bridges, a railway and motorway ones, connecting Bendery with the rest of Transnistria that is stretched along the left bank of the Dniester.

In 1992, the battle for Bendery was a turning point for the conflict. Under the pressure of Russian artillery and as a result of the negotiations between Moldova and Russia, a cease-fire agreement was signed.

A restored BMP, whose crew was killed in 1992 is a reminder of the battle as well as a bust of General Lebed. The Memorial of Memory and Sorrow is installed right before the bridges.

On May 9, Transnistrians lay flowers not only to those who died in the Second World War, but also to those who "defended Transnistria from the aggression of the Republic of Moldova".

The Russian Task Forces are especially warm-welcomed at the military parade. While the column passes through Suvorov Square, the current president of Transnistria Vadim Krasnoselsky talks about "the special merits of the Russian military in Transnistria".

"In 1992, after 47 years of peaceful living since the liberation from the Nazi and Romanian invaders, the war came to our land again, and it was only the Russian soldier who could stop the aggression against the Transnistria", Krasnoselsky commented.

Despite the pompous preparations for the parade and the increased popularity of the commemorations among citizens of Transnistria after the conflict in neighbouring Ukraine, the parade in 2017 looks rather modest – this time only the T-34 tank passed through the central square.

Although the truce has been maintained in Transnistria for 20 years, the region is still militarized. In Bender and Tiraspol, the capital of Transnistria, you can see a lot of military facilities closed for public eye with a sight "shooting prohibited" next to them.

A Russian military base in the centre of Transnistria capital is one of them. However, it opened its doors for visitors on May, 9 to show the reconstruction of the battle between German fascist troops and Soviet Army.

A military-patriotic education of Transnistrians begins with school. There is still an analogue of the Soviet "Zarnitsa" – the republican competition "The Young Patriot of Transnistria".

In Tiraspol I meet a former teacher of a military-patriotic school club at a "social market", an official name for a flea market. Mostly retired people sell old clothes, books and other second-hand stuff at this market. The former teacher, around 40, was selling soviet military antiques – medals, flags, uniform. Although he got redundant from his job in the school, he is still wearing uniform and chevrons of the patriotic club. When I mention the parade I saw earlier on he sighs: "A parade ... what about parade! The main thing is that the economy keeps developing".

The former teacher is a Ukrainian, like a third of the population of Transnistria, and has got two passports, like many others here. He is living between two houses – one is in Nikolayev region in Ukraine and another one is here, in Tiraspol. But he likes it in Transnistria better as it is "morally easier" for him here.

"I can walk around Tiraspol without any problems, no one forbids me to speak Ukrainian, and nobody tries to hit me when I wear Soviet badges or ribbons. I'm ashamed to be a Ukrainian because of those events in Donbass, I feel that here in Transnistria people condemn me silently. But not all Ukrainians are fascists, not all "banderovtsy", – the man says.

After the outbreak of the war in Donbass and the illegal annexation of Crimea by Russia, Ukraine is called an aggressor here, it is PMR official position.

The situation gets even more complicated when Ukraine agreed to introduce joint customs control with Moldova at Transnistria administrative borders.

PMR state TV is fear-mongering locals that these actions from Ukraine will bring Transnistria economy down. However, the region is well known for its contraband of cigarettes and spirits.

Patriots of Transnistria have been willingly helping building up "young republics" – "DPR" and "LPR" in Ukraine’s East. PMR politicians and military are actively participating in conflicts in Crimea and Donbas.

One of them is Colonel Valery Gratov got recently detained in Ukraine when he tried to get to Transnistria. He is the former head of the Security Service of PMR President Igor Smirnov, and known for training rebels in Donbass.

Another citizen of Transnistria, former Minister of State Security Vladimir Antufeev became the first deputy prime-minister of "DPR" on state security issues in 2014. At that time two more people from Transnistria special services Oleg Bereza and Andrey Pinchuk became Ministers of Internal Affairs and State Security in "DPR". All of them no longer occupy their posts.

In 2015, Alexander Karaman, the first vice-president of Transistria, became the Vice-Prime-Minister in "DPR" government on social issues. After his escape from "DPR", where he was prosecuted for kidnapping, he returned to Transnistira to become a Plenipotentiary Representative of the President of PMR in the Russian Federation.

The notorious "DPR" rebels battle commander whose forces seized Slovyansk, the leader of "Novorossia Movement" Ihor Strelkov, was also fighting in conflict in Transnistria on left-bank side.

Ukrainian military experts consider Transnistria potentially dangerous as the region can be used by Russia if it decides to further aggression against Ukraine.

Not so Soviet?

"Welcome to our little" Soviet Union"! – the travel agencies in Transnistria, which are few, promote the region as the last territory of the USSR alive.

Touring the Soviet Transnistria for a day will cost you around 20-25 USD. Guides will be glad if you pay in dollars – foreign currency is hard to get here. Many tourists come especially on May 9 to feel the atmosphere better.

Transnistrians in their turn are not against maintaining the image of the region as a museum of Soviet symbols.

"Let the state uses this in its own interests, let the tourists come in. If everyone comes here for a mini version of the Soviet Union, let them use it", says Anton Poliakov, 26-year-old documentary photographer born in Transnistria.

In his project he shows other Transnistria, that transforms – his generation of young people, people living in villages, on the borders.

"I'm trying to understand for myself what sort of people are Transnistrians? Who are we?"– explains Anton.

He says he loves Transnistria. As many of his friends he went to live in Russia, but returned eventually.

He is a geographer by education and learnt photography by himself. For his own inspiration and to inspire others he participates in the organization of the only documentary film festival in Transnistria on human rights called "Chesnok" (garlic).

The festival started in 2016 in four Transnistrian cities. This year’s programme included documentary movies showing in villages. Still the final stage of the festival takes place in Chisinau, in the premises of the Moldavian underground "Spalatorie Theater".

On the stage of a small theater hall an Iranian human rights activist, the main character of one of the festival's films, is answering questions from the audience.

Before that there was a documentary about Russian Channel one backstage. In this year’s programme you could also watch an Estonian movie on war reconstructions, a documentary from Romania about Romani deportation to Transnistria during Second World War and others – 10 documentaries in total.

The idea of the festival belongs to the activists of Tiraspol information and rights centre "Apriori". Anya Galatonova, 26, and Alexandra Telpis, 27, are among them. The organisers explain that the program was selected considering the specific nature of a Transnistrian spectator.

"Transnistria is complicated, you need to attract the audience, so that our spectator gets used to such events as "Chesnok" and have no stress when they hear the phrase "human rights". Therefore, we are very happy to host the festival in Chisinau. There are no problems and the audience is prepared. In addition, we have many friends in Chisinau – not everyone can come to Transnistria, but we can come here", – says Anya.

The conservative view Anya and Sasha explain as a "Soviet mentality". They themselves do not trust PMR authorities and believe that the state protects only itself but not people. The young women refer themselves to a new Transnistria generation which is open to everything new and can think critically. But they are a minority here.

"We are used to living here therefore do not understand how tight we are. You feel it when you go to Ukraine and Moldova", – says Olga Purakhina from Information and legal center Vialeks in Rybnitsa, Transnistria northern city.

The NGO is committed to improving the legal literacy of people.

In Purakhina’s opinion the lack of legal literacy is also a soviet legacy. In spite of the fact that Transnistria is a quasi-state, it is still possible to defend one’s rights in the court, Olga believes. She admits that Transnistrian legislation is mostly either a remnant from the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, or it contains rewritten abstracts from the Russian legislation. In some cases, she says, they forget to remove the "Russian Federation" from the text.

The main problems that people face in Transnistria are non-payment of wages and holidays, illegal dismissals, both in private and state companies.

The human rights activist, however, admits that Transnistrians are powerless in cases of human rights violations. One of the reasons, in her opinion, is the unrecognized status of the "republic".

Karolina Dutka, a 5th year student of the medical department in the University in Tiraspol, faced such a problem when she was doing her photo project about an LGBT community of Transnistria. She searched for her heroes of her project through friends and social networks, but it was difficult, since the topic of LGBT people in Transnistria is closed.

"Everybody pretends that LGBT doesn’t exist. But with the help of word of mouth I was able to talk to over 150 people. Among them there were not only students, but also adults, those who work, for example, in state institutions, teachers. Only 16 people out of those 150 agreed to participate in the project, still they wouldn’t disclose their faces", says Carolina.

After two months of photoshooting, Carolina announced an exhibition. The very next morning she received a call from an unknown person and was invited to a meeting at her University and asked to bring her passport. At the meeting the photographer was unequivocally told by a person from Security Service that the exhibition had to be cancelled, since this "contradicts the ideology of the state".

"In the end, they began to threaten me with problems at the University, with parents at work", says Carolina.

She was able to record this conversation and later published it. She decided to cancel the exhibition, and instead run it as online project which grew popular in Transnistria. After several months she counted 15,000 visitors on the website – a considerable number for Transnistria. Later on she held the exhibition in Odessa and Chisinau.

"I did not really believe that the KGB would be interested in what kind of exhibitions I was doing. I was surprised", Carolina tells about her reaction.

She is finishing her studies in Transnistria, making a new social photo project and planning to leave.

"I do not feel freedom of expression and creativity now, – says the photographer. When I have ideas in my head about projects, I immediately think if I will be imprisoned or not".

You can touch this feeling of censorship and self-censorship in the air. People are not willing to talk to strangers in the street, you can hardly see them protesting. It is the government that in fact has got the only right to organise street actions.

Frozen Language

Not only Soviet Symbols survived in Transnistria but also Moldovan language with Cyrillic spelling.

In 1989 Moldova voted for switching to Latin spelling. The Left bank interpreted that move as a threat, as Moldova was turning its head away from Soviet Union and towards Romania.

Then the idea of Transnistria breakaway state appeared.

Cyrillic Moldovan is one of three official languages, together with Russian and Ukrainian. You can find it on street name plates, names of the official bodies, in PMR passports, but you can hardly hear it in the streets.

In fact, it is rather a minority language in Transnistria and it’s becoming extinct as education and official communication is mostly in Russian. The language doesn’t exist anywhere else apart Transnistria, so parents rather teach their children in Russian-language schools. But there is also a possibility to learn Moldovan language in Latin spelling – a Romanian, in fact.

In PMR there are 8 schools where you can learn to write and speak Moldovan language in Latin alphabet. Theoretical Lyceum Alexandu cel Bun in Bender is one of them.

On the walls of the Lyceum there are portraits of Moldovan and Romanian writers, educators, poets, a portrait of Stefan cel Mare, a Moldovan prince whose statue stands in the center of Chisinau. The school’s timetable and all notes and signs are in Latin spelling.

The Lyceum has got three buildings and they are located on the outskirts of Bender. One of the buildings is adopted premises of a forestry. Apparently, life is not easy for this Romanian school in Transnistria.

Angela, a teacher of primary school, agrees to talk to me, however, she waves her hand in a tired gesture: "We talk but it goes nowhere". She confesses that there are less and less students each year – both due to demographic crisis in Transnistria and conflicts with local administration.

"Now we have many students from Russian-speaking families. They travel to school from Tiraspol and their parents think about sending them to study in Europe. Nowadays Russia is not as attractive as Europe. Politics is politics, but people need to survive", explains Angela.

Angela is a living witness of several blockades by PMR government that Lyceum lived through. The first one was in mid-nineties. Then the Lyceum teachers tried to save their school and organized the lessons right in front of the city administration, in the street. In 2004 PMR police again attacked and blocked Romanian-language schools.

Sasha and Kristina Telpis, then 14 years old, were among those who defended their Lyceum in Bendery. Kristina remembers how she and her sister came to the school yard to protect their rights to study in Romanian language.

"When the police went after school in Tiraspol, we realized that the same will happen to our school. At first, teachers came out to defend it, then students and some parents. Including me and my mother, because we had no idea where we else can continue studying", – says Christina and adds that it was a scary experience for her.

The schools remained under siege for several months. The PMR authorities cut off electricity, gas and water supply to them. The OSCE called the situation a "linguistic cleansing" then.

After the Lyceums got back to work, the oppression still remained. "When I spoke Romanian, I often heard other people saying "don’t you know how to speak normal language?", Sasha recalls. It was their mother who insisted on studying in Romanian language school so the sisters could continue their education in Romania.

Though these schools are situated on the territory of Transnistria, they are subordinated to the Ministry of Education of Moldova and have a private status.

The issue of Romanian-language schools in Transnistria has been a subject of political argument for "5+2" talks between Tiraspol and Chisinau for many years (the talks on conflict resolution with participation of Moldova, Transnistria, Russia, Ukraine, the OSCE, as well as observers from the EU and the United States).

Every September the schools face great problems.

The PMR government raises schools’ premises rental prices, maintenance fees, prohibits the import of new textbooks and equipment. During school lines, the students are not allowed to sing the national anthem of Moldova and put up a tricolour, the Moldovan flag.

Legalisation of Transnistria education in Moldova is another subject of long-standing bargaining between breakaway region and Moldova.

On the other hand, Russia is readily recognizes PMR diplomas. That is where a lot of students go to after they finish their education.

Others go to study to Ukraine.

Like Nikolay Kuzmin who graduated from Kyiv National Dragomanov University in Kyiv.

"The local diploma is merely an indicator that you studied. Not in any way a serious document that allows, for example, to study further at any university or getting a second higher degree by a shortened program or, even more so, teaching at a university. Secondly, the quality of Transnistrian education is low. I never heard any good recommendations about our University", Nikolay explains why he didn’t want to study in Tiraspol, his hometown.

Valentin Oleksienko received a diploma from the Transnistrian Engineering and Technical Institute.

"For a long time this was not a problem. I worked in Tiraspol by education. About two years ago I began to think of a possibility to move to another country. At that time Ukrainian salaries were even lower than in PMR, so I was thinking about Europe. Then I found out that I have no education, and to be able to legalize my diploma in Moldova, I will have to complete several more years of studying", says Valentin. The young man has got Ukrainian passport and was looking forward to implementation of visa-free regime with EU.

In another remote area of Bender, among private houses, there is a Ukrainian-language school. In 2003, Petro Poroshenko, current president of Ukraine, was at the opening ceremony, and till 2013 he took some care of it. He supplied the school with a computer class, a minibus for children.

Since the start of the conflict in Donbass, Poroshenko is not wanted here, the computer class is out of date, and the systematic support that Ukraine had promised did not work out.

Abandoned territories

"Where does Transnistria belong to?" I ask directly Zhenya, a young guy, who is renting out to me an apartment in Tiraspol.

"Where to? Moldova, of course!", Zhenya admits and explains that even though many here like Russia, but Russia does not do much for Transnistria.

Moldova remains the main export destination for the PMR – almost half of Transnistria's goods go there, according to the data from the Ministry of Economy of PMR for 2016. On the second place is Ukraine, where more than 11% of goods are sold. The EU share also accounts for almost a third of exports.

The supply to the Russian Federation is only 8%. At the same time, the budget of Transnistria depends significantly on Russian subsidies and the region has a $ 7 billion debt for gas to Moldova.

"Here is only one owner – "Sheriff" company. This belongs to "Sheriff", and that is too", Zhenya grims while pointing out to me the factory of local brandy KVINT, a supermarket chain Sheriff, a textile company Tiretex and other various buildings in the city centre.

"Sheriff" holding is controlled by oligarchs Viktor Gushan and Ilya Kazmaly. The company, in fact, covers all spheres of the economy from banks and the media, to communications, trade and sports. According to data for 2015, every third PRM rouble in the "republic’s" budget comes from the companies of the "Sheriff" holding.

You can hardly find "Sheriff" competitors. One of them is Furshet supermarket in the center of Tiraspol. There is also Moldovan catering chain in Transnistria – Andy’s and La Placinta cafes.

City lights throughout the city are advertising "Sheriff": from the construction of sheep farms to sports and social programs. In fact, those who try to compete with the oligarchs' business are squeezed out of the market. The practice of business raiding is widespread. Currently the owners of three companies are suing the state to regain their businesses. The head of one of these companies Agro-Luka got deported from PMR.

"It’s like in communism. But this can not last forever! People will get tired eventually", believes Zhenya.

The flats rental is his family business and it is very small – they have three apartments in Tiraspol as demand for accommodations is small here. In the city you can spot few more small businesses like cafes, car repair, grocery stores. There is also a lively trade on the market with products from vegetable gardens.

Despite the fact that over the past 25 years about $ 15 billion has been invested in the economy of Transnistria, the region looks very much outdated. The only modern building is the training base of FC Sheriff, which plays under the flag of Moldova. Otherwise, there are old Belarusian trolleybuses, soda machines, buildings and signboards that have remained, it seems, since Soviet times.

"Transnistria with Russia" banner hangs on the building of Tiraspol central cinema. Russia, in turn, does not hurry to accept the region and does not recognize it either.

After "big Putin’s friend" Ihor Dodon had been elected as president of Moldova he offered Transnistria a federalization scenario. However, Vadim Krasnoselsky, also the newly elected head of the unrecognized republic, said that Tiraspol is not interested in Moldova's proposal as PMR wants independence and unification with Russia. 97% of the Transnistrians voted for that in referendum in 2006.

"I do not really believe that some day someone will allow Transnistria to become an independent state, – says the human rights activist Olga Purahina, – Russia will always try to expand its influence here, because this is a great strategic point".

"My mother believes that now Transnistria is an abandoned territory, – says Anya Galatonova, – My parents' mentality is such that they believed in something unified, whole, and then we were cut off, and we do not know what to do next. And they feel offended, that Russia separated from us".