Russian leaders see potential truce as a lifeline for struggling economy

Moscow is carefully concealing its vulnerabilities as it moves towards the heart of the negotiations on freezing the Russo-Ukrainian war, with the economy being the most pressing concern.

As Moscow approaches the heart of the negotiations on freezing the war in Ukraine, it is carefully concealing its vulnerabilities, particularly those related to its losses of military personnel and equipment, alongside declining public support for the war. But it is the Russian economy that has taken the heaviest toll.

The Russian war economy functions by its own rules and is characterised by unproductive frontline consumption on a massive scale. It consumes vast resources that could otherwise be allocated to produce useful goods for civilians. Civilian output is sacrificed in favour of military production.

And someone has to bear the cost of the frontline demand. Initially, the state covers it, although the burden has been shifting to the population as the war drags on. The burden is lighter if there are external sources of economic aid, and heavier if there are none. Russia is currently dealing with the latter scenario.

The cost of the war

Russia's military spending in 2024 was nearly triple that of 2021, rising from RUB 5.9 trillion (around US$73.1 billion) to RUB 16.2 trillion (US$200.7 billion). Three years of full-scale war have cost the Kremlin RUB 37 trillion (nearly US$458.6 billion), which is RUB 21 trillion (US$260 billion) more than in the preceding three years.

In 2024, military expenditure accounted for 40% of Russia's federal budget and approximately 8% of its GDP. These levels are reminiscent of the last years of the Soviet Union, when it was caught up in an arms race with the United States that ultimately it could not win economically.

The Russian economy has also been hit by the effects of sanctions. The most apparent are the freezing of Russia's reserves and restrictions on gold sales. In February 2022, Russia's gold and foreign exchange reserves totalled US$631 billion. Now Moscow has access to just US$86 billion: around US$300 billion, and US$28 billion in the IMF, has been frozen by Western powers. Additionally, its ability to sell gold valued at US$196 billion is now restricted.

Where does the money for the war come from?

Russia's primary source of income – and the key source of funding for military operations – is energy exports. The Russian government also draws on funds from the National Wealth Fund (NWF) and issues currency. Moscow's gold and foreign exchange reserves held abroad are currently unavailable for these purposes.

Prior to Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, exports of oil and petroleum products generated US$170-210 billion in foreign exchange earnings annually, accounting for about 40% of Russia's total exports. In 2024, this figure stood at US$195 billion, consistent with pre-war levels, though lower than the record results of 2022 (US$230 billion). In 2025, revenues from oil and petroleum product sales could decline to US$140-150 billion due to falling oil prices.

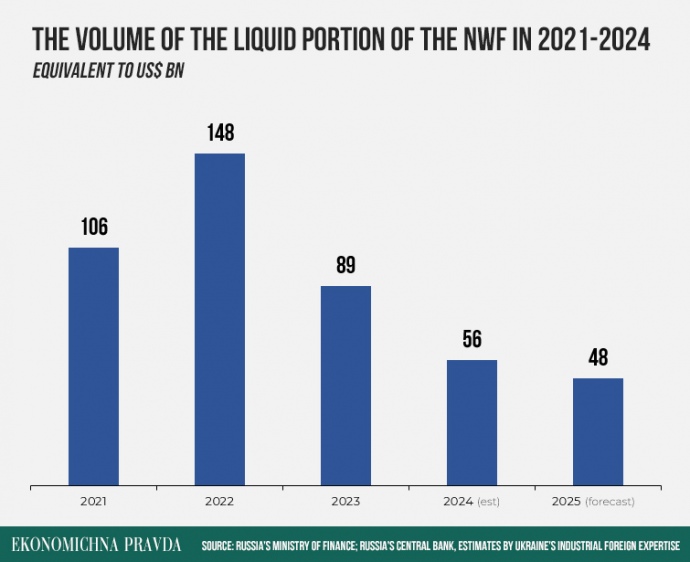

Russia was obviously preparing for war, and consequently by May 2022, it had accumulated about US$148 billion in the NWF thanks to additional revenues from oil exports due to high prices globally. By early 2025 there was only US$35 billion left in the fund: 164 billion yuan (approx. US$22.7 billion) and 179 tonnes of sanctioned gold.

If money had continued to be withdrawn from the NWF at the same rate as in 2022-2023, it would have been empty by the end of 2024. However, Russia opted not to exhaust the fund and instead chose to cover part of its budget deficit by issuing currency.

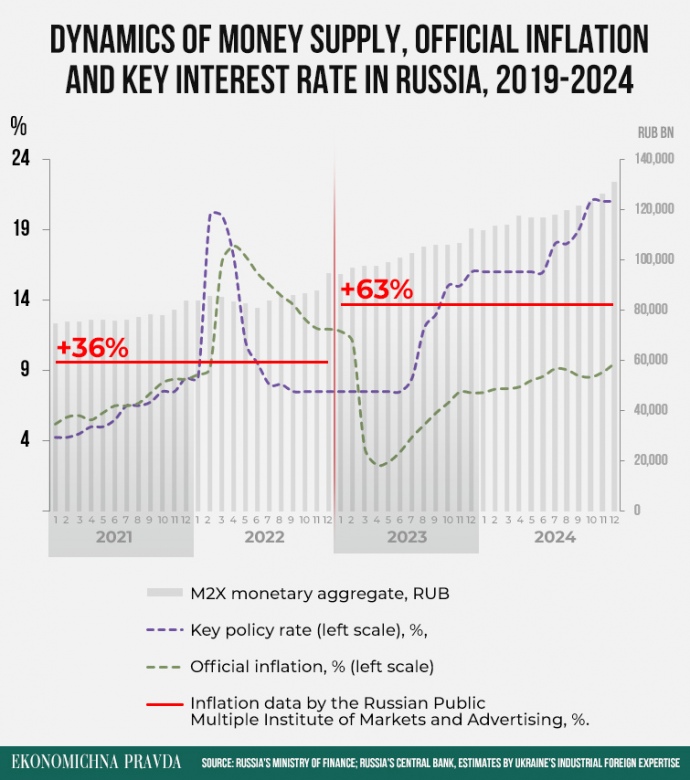

There has been a significant increase in the intensity with which Russia has been printing money. Between 2022 and 2024, the volume of the money supply (broad monetary aggregate M2X) surged from RUB 83 trillion (roughly US$1.03 trillion) to RUB 131 trillion (US$1.62 trillion), marking a 63% increase. This is notably higher than in the equivalent period before the war (+36%).

In peacetime, money is printed as the economy grows to service the added value created. However, even the official data in Russia shows only moderate GDP growth, and the increase in the money supply is several times higher.

Russia finances its military spending by issuing money, with most of it going to people employed in war-related sectors – defence industry workers and military personnel.

However, there is an insufficient supply of goods to anchor these funds in the economy. This is primarily due to the decline in domestic production caused by the withdrawal of Western companies. The growth of Chinese imports is also hampered by Western sanctions driving up costs and increasing delivery times.

All of this fuels inflation, which officially stands at 0.2-0.3% per week, or 10-12% annually. In reality, however, it could be as high as 25-28% per year, as alternative analyses and the Russian Central Bank's key interest rate of 21% per annum would suggest. There would be little reason to keep it so high if the official inflation figures were accurate.

Read also: More trouble ahead: as Russia enters 2025, how is the economy doing?

The fact is that the war Russia is waging against Ukraine is based on mercenaries: a contract soldier earns around RUB 5 million per year (approximately US$61,900), comprising a sign-on bonus of RUB 1-2 million (US$12,400-24,800), and a monthly salary of RUB 250,000-300,000 (US$3,100-3,700). This is significantly higher than civilian salaries: doctors and teachers, for example, typically earn RUB 35,000-50,000 (US$430-620) per month.

This stark income disparity and the imbalance between supply and demand point to deep fractures in the Russian economy. The root cause is clear: soaring military spending amid dwindling sources of war funding that do not involve printing money.

How the start of the war compares with today's reality

Russia no longer has the same sources of funding for the war that it did at the outset of the full-scale invasion. The National Wealth Fund has dwindled to US$35 billion and oil export revenues have declined. In April 2025, the price of a barrel of Russian Urals oil [Russia's oil benchmark] was US$17 lower than the previous year. Consequently, export revenues are expected to fall by US$40-50 billion.

Even Russia’s Economy Ministry has acknowledged that this year, the price of a barrel of oil will be US$56, a significant drop from the earlier forecast of US$69.50 which the budget was based on.

Despite this, Russia must ramp up military spending to meet its objectives in the war in Ukraine. For example, it needs to fund the production of new equipment, as stockpiles of older hardware have been exhausted. This year, this expenditure could reach RUB 20 trillion (about US$247 billion): RUB 16.5 trillion (US$204 billion) has officially been budgeted, although this figure is likely to be surpassed if previous years are anything to go by.

Stuck in this challenging situation, Moscow has resorted to issuing money. The Russian Central Bank has now switched to weekly repo operations, effectively issuing targeted funds to commercial banks to purchase government bonds. This will create additional inflationary pressure.

The only ways out are to cut war spending or obtain external financing. But either would require a halt to the active phase of hostilities. In that case, Russia would likely attempt to have the pressure of sanctions eased in order to generate additional revenues from oil exports.

Certainly, the Donald Trump phenomenon – and particularly his desire to rethink the current sanctions regime – could change everything. However, in the current environment, this would be perceived as pandering to – or more precisely, saving – the aggressor. Until that happens, time is running out for the Kremlin's economy, and as a result, the economic situation in Russia is expected to deteriorate even further over the summer.

Author: Volodymyr Vlasiuk

Translation: Artem Yakymyshyn

Editing: Teresa Pearce