Erased Generations: How Russia recreates imperial instruments of influence

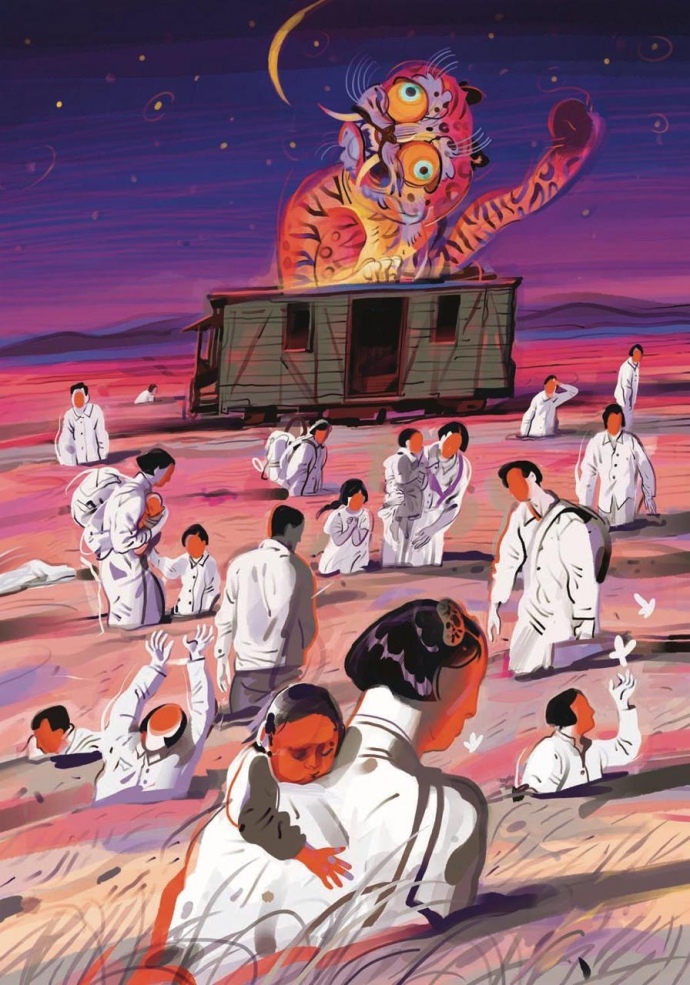

There are many ways to erase a person. This has been vividly demonstrated by Russia in its imperial form for over 300 years. Back in the eighteenth century, thousands of Ukrainians were taken away by order of Peter the Great to build St. Petersburg and the Ladoga Canal.

There are many ways to erase a person. This has been vividly demonstrated by Russia in its imperial form for over 300 years. Back in the eighteenth century, thousands of Ukrainians were taken away by order of Peter the Great to build St. Petersburg and the Ladoga Canal. The Russian Empire used forced evictions: about 13K people were deported from Eastern Galicia in 1914-1915, and in Stalin's time people were also forced to put their entire lives in a symbolic suitcase in minutes, as "nationality" became a sentence. Hundreds of thousands of representatives of different nationalities within the USSR were subjected by terror.

The deportations of ethnic Germans, Poles, Jews, Pontic Greeks, Crimean Italians, Circassians, and Turkish Meskhetians are tragic proof of a practice that erased the histories of entire generations. It is the indigenous peoples of Ukraine who have fully experienced the consequences of Russian policy, which for centuries has only changed signs.

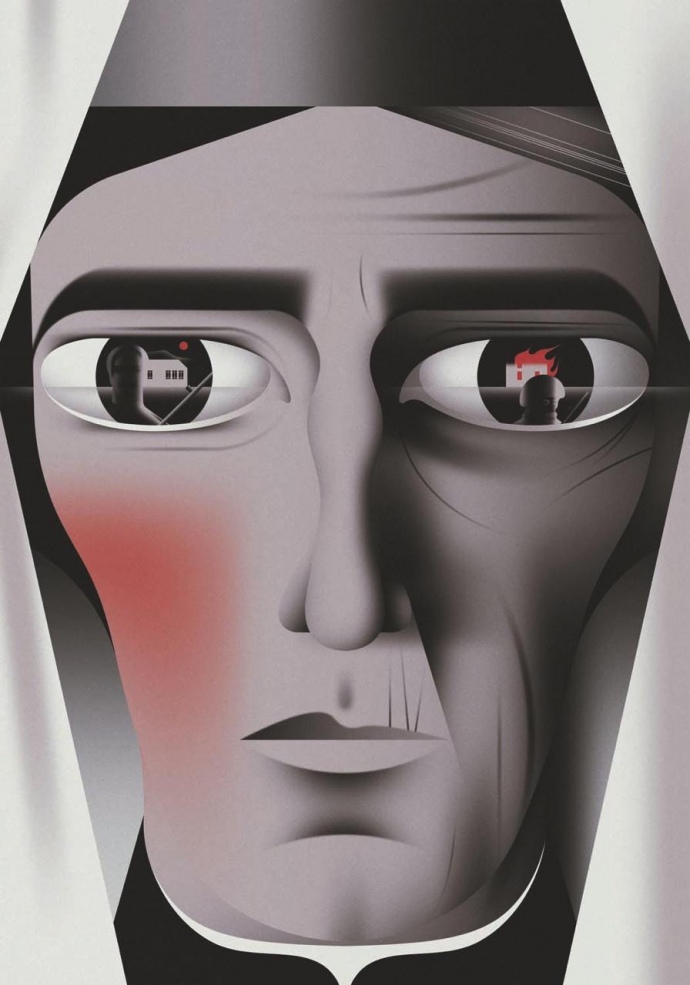

Today, the methods are the same, just a new form. The passport replaces identity. Through "manual" organizations of national minorities, Russia buys political loyalty to strengthen its influence. At the same time, ethnic minorities are often forcibly sent by the Kremlin to war to fight against their own people in Ukraine and die. What is happening today through passportization, manipulation, and war, the Bolsheviks once did through censuses, maps, and "Soviet colonization."

How classification led to deportation

Before 1917, the Bolsheviks called for national self-determination for all peoples and condemned colonization as exploitation. However, after coming to power, they realized that Soviet Russia could not survive without the cotton of Turkestan and the oil of the Caucasus. In order to combine anti-imperial slogans with the desire to preserve all the lands of the former Russian Empire, the Bolsheviks integrated the national idea into the administrative and territorial structure of the new Union.

With the help of former imperial ethnographers and local elites, they organized all the peoples of the empire into an official grid of nationalities while recognizing and controlling their identities. This is how the program of "Soviet colonization" was born.

The Bolsheviks had great ambitions, but they lacked knowledge about the lands and peoples. So they were forced to rely on former imperial experts, ethnographers and economists educated in the European intellectual tradition. Many of them had studied in Europe.

Like the Bolsheviks, these scholars believed in the power of rational governance and saw Russia through the prism of European experience. That is why Vladimir Lenin entered into an alliance with them to help spread the revolution and find a way to national policy. A key tool was the Commission for the Study of the Tribal Composition of the Population, established in 1917. Its ethnographers not only collected data, but also organized censuses, defined borders, led expeditions, and prepared exhibitions and courses on the topic of "Peoples of the USSR."

In the European colonial empires, as the American historian Francine Hirsch notes in her book Empire of Nations, anthropologists usually played a secondary role. In the USSR, however, they became the true architects of national policy. Their work allowed the Bolsheviks to build their own "civilizing mission", an evolutionist state program that combined the Marxist doctrine of historical stages with Western theories of cultural development. The Soviet government invested huge resources in the project of "ethno-historical evolution." It actively "rooted" local institutions, training Uzbek, Belarusian, and other "national communists" to work in the republics and regions. But at the same time, it destroyed traditional culture and religion, tore communities apart, and persecuted those who showed "spontaneous nationalism." Entire communities were imprisoned or exiled, and many were executed for trumped-up charges of "bourgeois nationalism."

The census, maps, and museums formed a triad that the Soviet regime had to bring together. Despite all efforts, in the 1920s they didn’t yet form a single mosaic: many peoples included in the official list of "nationalities" were not reflected either on maps or in museum halls. The Soviet Union remained a "project in progress," and Soviet ethnographers spent two decades looking for ways to combine the census, borders and museums into a common image of the "new state."

This image was created through "double assimilation." This is the name given to this process by Francine Hirsch. First, by including a diverse population in the category of "nationalities." And then – by the integration of already nationally classified groups into the Soviet state and society. Formally, it was about the self-determination of peoples, but in practice, the census and the delineation of borders were instruments of discipline and control.

New national territories, schools, and cultural institutions proved to be effective mechanisms for integrating non-Russian peoples into a single Soviet space.

At the same time, museums, especially ethnographic museums, became laboratories where official narratives were formed and disseminated. It was there that the empire was transformed into the "Union," emphasizing that the development of nations was taking place under the auspices of Soviet power. Visitors were encouraged not only to watch but also to imagine themselves as part of the new Soviet history. They were even asked to express "socialist criticism" of the exhibits to make the process of creating the official narrative seem collective.

Today, Russian propaganda and media in the occupied territories are doing the same thing, simultaneously looting Ukrainian museums and taking away archives to control historical memory and entrench the power of the aggressor state.

It is important that this process was not only imposed from above. Double assimilation worked as an interaction: categories and narratives were created and activated with the participation of experts and people themselves. For example, preparations for the 1926 All-Union Census included all-Union discussions between Soviet officials, scholars, and local elites about which peoples should eventually be included in the official "List of Nationalities of the USSR." The census itself was conducted through interviews and for many people this was the first lesson in "official identity": how to correctly identify themselves in the form.

The same was true of the borders: interagency commissions for delimitation and delimitation consulted with scholars and elites, and collected petitions from communities. Local elites, seeing the delimitation as a chance to gain territory and resources, actively promoted the Soviet "national idea" among the population, while integrating the population into the overall system.

Already in the 1930s, Soviet ambitions and borders were threatened: Japanese invasions of the Far East and Nazi claims to ethnic Germans in the USSR challenged the regime. The Nazis and their allies undermined the Soviet project of socialist transformation on two fronts. The spread of national socialist ideas after 1930 and the consolidation of Nazi Germany in 1933 forced the Soviet regime to accelerate its pace of action.

At the same time, the USSR sought to protect borders and strategically important regions from "unreliable elements," including "diaspora nationalities" Germans, Poles, and other groups whose homelands were outside the Union. The boundary between "Soviet" and "foreign" nations was rigid, and those who fell into the second category were subject to deportation. In this way, the Soviet regime simultaneously rejected biological determinism and punished people for having the "wrong" ethnic origin.

Deja vu from the past on Crimean land

Deja vu from the past can be felt today in Crimea. Russia uses similar mechanisms in the occupied territories: Kremlin pockets minority organizations and funds cultural projects and publications to increase its influence and shape the "right" narrative about history and identity. For example, the regional public organization "Community of Italians of Crimea "CERKIO" was officially registered in Kerch in 2008. However, its origins date back to the early 1990s, when the first initiatives to restore the identity of Crimean Italians appeared on the peninsula after the collapse of the USSR.

Paradoxically, it was during the Russian occupation of Crimea that in September 2015, representatives of the Italian community, with the assistance of the new "authorities" of the peninsula, met with Russian President Vladimir Putin and former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi. And the very next day, on September 12, Putin signed Decree No. 458, which officially included Italians in the list of deported peoples subject to rehabilitation.

This gesture looked like a belated act of justice recognition that had been waiting for decades. But it clearly had a political overtone: at a time when Russia was trying to consolidate its dominance in Crimea, such "recognitions" became a tool for soft integration and an attempt to gain loyalty among national minorities. The memory of the tragedy became a bargaining chip in the hands of the new bloody colonizers.

The fake decree on the "rehabilitation of the peoples of Crimea" was signed in April 2014, immediately after the occupation. The Italians were added a year later only politically and demonstratively.

However, the Italians of Crimea received not only formal "recognition" - soon their community received a presidential grant from Vladimir Putin to research their own history of deportation. With this money, the book "Italians of Crimea. History and destinies" written by Giulia Giachetti-Boyko and Stefano Mensurati was published in occupied Crimea. The publication contains numerous memoirs, archival materials, and family photographs. This is definitely a work of memory. But at the same time, it is a work in conditions where memory is turning out to be an instrument of Russia's colonizing policy in the 21st century.

This is not an accusation. This is an omission. A historical lesson for which one day we will have to pay. As well as for the fact that today, in Italy, a country with which so many descendants of Crimean Italians associate their identity, the truth is being rewritten in silence.

In school geography textbooks for the 7th grade, Crimea is labeled as Russian territory, and the war in eastern Ukraine is referred to as an internal conflict. None of the more than sixty textbooks published between 2010 and 2024 mention the occupation or violations of international law. And these are read by thousands of European schoolchildren who are just forming their understanding of the world.

Even such a small example shows that Russia's pretended "care" for the Italian community in Crimea is just an attempt to whitewash its own crimes, both past and present. Formal gestures of "recognition" are used not to restore justice, but as a tool of political manipulation, which should finally legitimize the occupation in the minds of Europeans and disguise repression.

This once again emphasizes the complexity of the process of understanding the past, in which personal memories, official history, and the current political context often exist in parallel planes.

Author: Volodymyrа Kanfer, journalist and author of the "Erased Histories" project of the NGO PR Army.