Criminalized and invisible: the long fight of queer Ukrainians

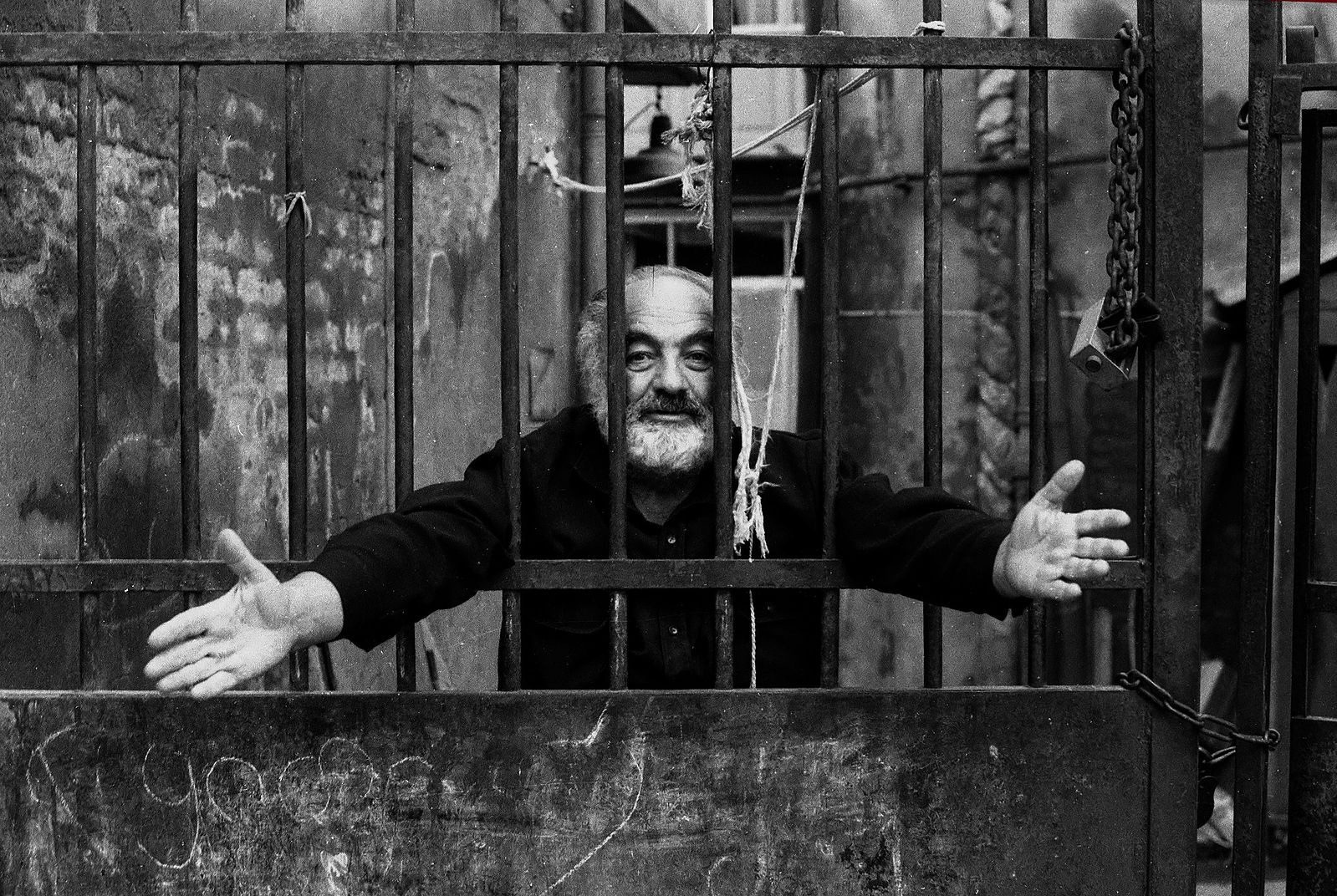

On a summer evening in the late 1980s, Kyiv’s central boulevard looked like any other. Couples strolled Khreshchatyk Avenue, children licked ice cream, the air smelled faintly of petrol and dust. But to those who knew, a narrow hundred-meter stretch near the city hall was something else entirely: a meeting point for men who desired men. A look, a gesture, a sentence carefully dropped could lead to companionship. Or to prison.

"In Kyiv, it was the hundred-metre strip of Khreshchatyk near the city hall. In Lviv, it was the promenade before the opera house," recalls Andriy Kravchuk. "Everyone knew, but only in our circle. You could meet someone wonderful – or you could meet a police informant."

For decades, same-sex intimacy in Soviet Ukraine was not simply taboo – it was criminal. Article 121 of the criminal code, known by its Russian term muzholozhstvo, made sex between men punishable by up to five years behind bars. The law did not have to be enforced constantly to be effective. Its shadow was enough. The possibility of arrest, blackmail, or exposure kept people in line.

Women were not covered under the same statute, but invisibility and psychiatry did the job instead. Lesbian relationships were treated as a form of mental illness. Women could be detained in psychiatric hospitals, subjected to "treatment," or simply erased from official reality.

"It was a forbidden subject," says Kravchuk, now an expert at the LGBT Human Rights Nash Svit Center. "You could not find a single book, a single article, not a word on television."

Growing up in Luhansk, Kravchuk’s early youth was a world of silence: as he could not find any information on what it meant to be gay or meet other gays in the open.

"I knew I was different, but I couldn’t name it. I searched encyclopedias. Nothing," he remembers. "It was only around the time the USSR was collapsing when you started hearing certain things being spoken more freely, but it was still a very hushed subject. Like in every totalitarian society, people learned to survive by building secret circles, by knowing whom to trust."

Queerness as Crime and Pathology

The Soviet system treated queerness as both a crime and a disease. For men, Article 121 provided the legal instrument for imprisonment. For women, psychiatry became the weapon. Doctors classified homosexuality as a mental disorder until 1990. Women caught in intimate relationships could be forced into psychiatric institutions, subjected to electroshock therapy, heavy medication, or so-called "corrective" treatment.

Such treatment was a direct result of the authoritarian rule and a reported hatred toward gays shared by Stalin, who was extremely homophobic. Homophobia went hand-in-hand with mass repressions,when it became law during the height of 1930s purges and mass executions. "Sodomy" – as this was how gay relations were called – became a criminal liability in 1933. Sexual relations between men were punishable by imprisonment for 3 to 5 years. In 1961, a "lighter" version of the punishment was introduced – so gay men could be imprisoned for up to 1 year, or sent to camps for three years.

Gay relations between women were not a crime, but lesbians were punished, too. Instead of jails, lesbians were sent to psychiatric hospitals by force. There, they were treated with medications that affected their mental state and coherency, and upon release, had to be registered with the local psychiatrist as mentally ill.

Talking about gays or homosexuality in public was impossible, and many people did not even know it could exist. What’s more, many gay people had a difficult time understanding who they were simply because there was nearly no information or possibilities to meet other gays.

Journalist Kateryna Farbar, who collected oral histories of lesbians in Ukraine, tried to gather stories of lesbian Ukrainians who lived in the late Soviet period.

"Especially among women of the 1980s, you could collect very little information, because sexuality was very suppressed," she says. "The women didn’t speak openly, sometimes they didn’t even fully realise their homosexuality themselves."

The law’s uneven enforcement created a constant, gnawing fear. Some years saw relatively few arrests. In others, waves of prosecutions reminded everyone of the risks. The uncertainty itself was part of the control.

"If a gay man was murdered, the police would interrogate everyone he knew," Kravchuk says. "If someone confessed, it could ruin a whole family. They didn’t pursue every case, but the fear – it was always there."

Cultural Erasure

Homosexuality did not exist in Soviet culture, at least not openly. Encyclopedias contained no entries. Popular films and literature presented only heterosexual families as legitimate. When queerness appeared, it was coded or demonized: decadent Western spies, morally corrupt foreigners, deviants. For Soviet citizens, there were no positive references, no cultural mirrors.

And yet, queer presence surfaced in oblique ways. In cinema, the lush visual style of Serhii Paradzhanov set him apart. His 1965 masterpiece Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, shot in the Carpathians, won acclaim abroad but drew suspicion at home. In 1974, Paradzhanov was sentenced to five years in a labor camp under Article 121. His homosexuality provided a convenient pretext. His real offense was his refusal to conform. As Kravchuk explains, gay relations could be tolerated by the NKVD and Soviet authorities as long as the so-called gays were loyal to the party and hid their sexual orientation. However, liberal and free-thinking artists or activists were not to be trusted by the authorities – and if they happened to be gay, this could be used against them as a silencing tool.

Such cases were rarely publicized in Ukraine. Most people never heard the details or even knew of imprisoned dissidents. But for those in the know, the message was unmistakable: queerness made you vulnerable to state punishment.

Survival and Secret Networks

Survival demanded ingenuity. Some queer Ukrainians entered marriages of convenience. Gay men and lesbians paired up, providing each other with cover. "Valeriy Leontyev, a famous Soviet singer, told us he was gay," Kravchuk recalls. "He married his bass guitarist, who was a lesbian. It was just a cover. They didn’t interfere with each other."

Others turned to pleshki, clandestine meeting points in public spaces. A stretch of boulevard, a park bench, a corner near a monument – all could serve as gathering spots, invisible to outsiders but legible to those in the know.

"You learned of those places from people who were already in the know, so it was a slow process to build community," Kravchuk says.

The risks were high. A stranger might be a fellow traveler – or a police informant. Raids were not constant, but they happened. And because secrecy was paramount, relationships often remained anonymous.

"People sought out their own," Kravchuk explains. "Anonymous contacts were often the safest, because you didn’t exchange names. Always there was risk. But people found ways. Like in every totalitarian society, niches formed where people survived."

Dissidents’ Silence

If queers were marginalized by the state, one might expect them to find support among dissidents. But political dissidents did not extend solidarity. Groups like the Ukrainian Helsinki Union, which campaigned against censorship and for religious rights, rejected queer issues. For them, fighting for equality for homosexuals was not a priority, and gay rights were excluded from human rights agenda of most civil society initiatives of the late Soviet period. When Western allies urged Soviet dissidents to defend gay men imprisoned under Article 121, many refused. Some dissidents feared that associating with queers would discredit their cause in the eyes of ordinary citizens.

When Ukraine declared independence in 1991, it abolished Article 121, becoming the first post-Soviet republic to do so. The effect was immediate. The police could no longer prosecute people simply for same-sex relations. A new space opened, however fragile.

"The nineties were like an explosion," Farbar says, "There was hunger to meet, to organize. People were building a community in real time."

The new community was messy, improvised, joyous. Parties took place in rented basements. Lesbian groups organized football tournaments. Queers claimed corners of straight bars, carving out their own spaces.

"There was a need to find each other, to create their own spaces," she explains. "But sustaining them was hard – women had fewer resources, and less money. Gay men’s bars survived; lesbian spaces usually didn’t."

Without the internet, presence was everything.

"In the nineties, because there was no internet, there was a greater need to gather somewhere, to organize women-only or homosexual spaces," Farbar says. "[Now], with the internet, and greater safety and visibility, the need remains, but lesbian women don’t have the economic resources to create such spaces."

The first organizations appeared, often under the guise of HIV-prevention projects.

"It was the only way to be recognized," Kravchuk explains. He co-founded a group in Luhansk in 1997, which became officially registered in 2000. In Mykolaiv, activists built what became the largest queer NGO in southern Ukraine.

But the early movement was fragile. A national group, Hanimed, collapsed after mishandling an international conference. "It created a negative image in the eyes of the international community," Kravchuk says. "For several years, our contacts with Western organizations were damaged."

The HIV/AIDS crisis added another layer of stigma. With little public knowledge, gay men were often blamed. For NGOs, focusing on HIV prevention provided a way to operate legally, but it also reinforced the association of homosexuality with disease.

The Independence, Euromaidan, and War

By the early 2000s, new organizations were more stable. Media coverage shifted.

"Suddenly I realized journalists had become our first allies," Kravchuk says. "They wrote less sensationally, more accurately. That mattered."

But hostility endured. The Orthodox Church and other religious groups started talking about homosexuality as a vice and became very vocal in their criticisms of gay relations or marriage equality.

"Homophobia became a cultural trait," Kravchuk explains. "Not ideological – cultural. The revival of religion in the 2000s worsened things. The churches filled the role once held by the Communist Party, and they found their new cause: fighting gays."

Far-right groups began to organize. Attempts to hold public marches often ended in violence. Police protection was unreliable. Queer activists were attacked in the streets, events were disrupted, and organizations learned to operate cautiously.

In 2012, parliamentarians from across the political spectrum introduced a bill to ban "homosexual propaganda," modelled on Russia’s law. "It almost passed," Kravchuk recalls. "If not for Euromaidan, we might have gone down that road."

The Revolution of Dignity in 2013-2014 stopped the bill and shifted Ukraine decisively toward Europe. But Russia’s annexation of Crimea and war in Donbas changed queer life again.

Activists began to connect their struggle with broader democratic movements. For the first time, Kyiv Pride marches were held with significant police protection. Attendance was small, but the symbolism was large. Later, Pride parades expanded to other Ukrainian cities, and LGBTQ+ organizations mushroomed across the country.

The Russian invasion of 2014 also brought queer Ukrainians into new visibility as soldiers and volunteers. The stereotype of queers as weak or alien to the nation was challenged by reality on the front lines.

Writer and veteran Alina Sarnatska witnessed this firsthand.

"In one military unit, there was one very radicalized guy serving together with a bisexual man," she recalls, "In front of my eyes, I could see how, because they were serving together, they gradually moved from petty arguments to a point where they could live with people with completely different views as in the same family".

Sarnatska recently wrote a book titled Who United Love and Courage, which is about Ukrainian queer veterans, where she highlighted stories from gay servicemen and servicewomen as well as experiences of their comrades who became allies.

She realized these transformations mattered.

"Their willingness to dialogue, their unwillingness to accept propaganda, hatred, and so on, were crucial," the author says, "That’s what makes us human. That’s humanity, that’s kindness."

The Urgency of Recognition

The full-scale invasion of 2022 brought new urgency. Same-sex partners of soldiers killed in combat are left without compensation, inheritance rights, or even notification.

"I’ve lived with my husband for twenty-seven years," Kravchuk says. "We’ve survived everything. And yet, I still can’t marry him in my own country. That is absurd."

Public opinion has shifted, especially among the young, but politics lags behind.

In March 2023, Inna Sovsun, a member of the Holos party, introduced a draft law to establish registered partnerships for same-sex and different-sex couples, granting them legal recognition. This means similar rights to other married couples, such as the right to inheritance, property rights, and medical decision-making privileges.

Despite initial support, including a petition with over 25,000 signatures and backing from President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the bill has encountered significant opposition. Conservative factions have stalled its progress, citing concerns over constitutional definitions of marriage and religious protests.

"Ukrainian MPs are more conservative than the people they represent," Kravchuk notes. "Many admit privately they’d vote for partnerships, but they fear priests campaigning against them."

According to the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, around 55% of Ukrainians do not oppose civil partnership for same-sex couples vs. 35% of those who are against their legalisation. Furthermore, the recognition of same-sex partnerships is indirectly tied to Ukraine’s European integration, given the EU’s focus on equality and human rights.

Russia’s war has clarified the stakes. Patriarch Kirill describes the invasion as a crusade against "gay parades." Putin insists it is a defense of "traditional values."

"So now, for us, there’s no choice," Kravchuk says. "Either we build a modern European democracy, or we disappear. Millions of Ukrainians now see that those who attack queer people are the same ones attacking Ukraine. The link is clear."

Ukrainian soldiers at Pride in Kyiv.

Farbar emphasizes that queer organizing is not new.

"People abroad think Ukrainian activism started only yesterday," she says. "It hadn’t. There are dozens of organizations, some founded in the 90s. There are a lot of events. The visibility is real. And the need for equality, especially in wartime, is urgent."

For Sarnatska, the meaning is distilled into two words. "Love and courage… that’s what unites us. That’s what carries us through."

Author: Anna Romandash

This publication was produced with support from n-ost and funded by the Foundation Remembrance, Responsibility and Future (EVZ) and the Federal Ministry of Finance (BMF) as part of the Education Agenda on NS-Injustice.