Foxhole is your second home: what infantrymen feel before going into combat and how they endure 99 days on the front line

The nature of the Russia-Ukraine war is constantly changing, and the development of technology is playing a significant role in this.

From November 2024 to May 2025, fighters of the Khartiia Brigade carried out a successful offensive operation, pushing the Russians back from Lyptsi, a strategically important settlement north of Kharkiv, and moving the front line further away on this front. Meanwhile, access to frontline areas has become significantly more challenging over the past year – primarily due to the use of drones in swarms and new modifications, such as the use of drones using fibre optic cables to avoid being their radio signal being jammed.

Last summer, the Ukrainska Pravda team visited the Lyptsi front, where the Russians had just launched an offensive. The team went to the settlement of Slobozhanske. Back then, the line of contact was just four kilometres away, yet the team was able to move around there relatively freely even in broad daylight. Now it is dangerous to move around not only Slobozhanske, but also Borshchova, which is twice the distance from the front line.

For the military, getting to their positions has become a new quest. Moreover, leaving those positions is even harder. Sometimes infantrymen are forced to remain at the very front line for weeks, or even months, as rotations are not carried out to avoid exposing them to even greater danger.

The Khartiia Brigade’s communications officer and regular Ukrainska Pravda contributor, Dmytro Kuzubov, spoke with the brigade’s infantry: with those who will be heading into combat within hours after the conversation, and with those who had returned after three months at the front. He asked what they have to overcome to reach and leave their positions, what they think about while they’re in a foxhole, and what they feel after the long-awaited return from the front line.

"Everyone out here!"

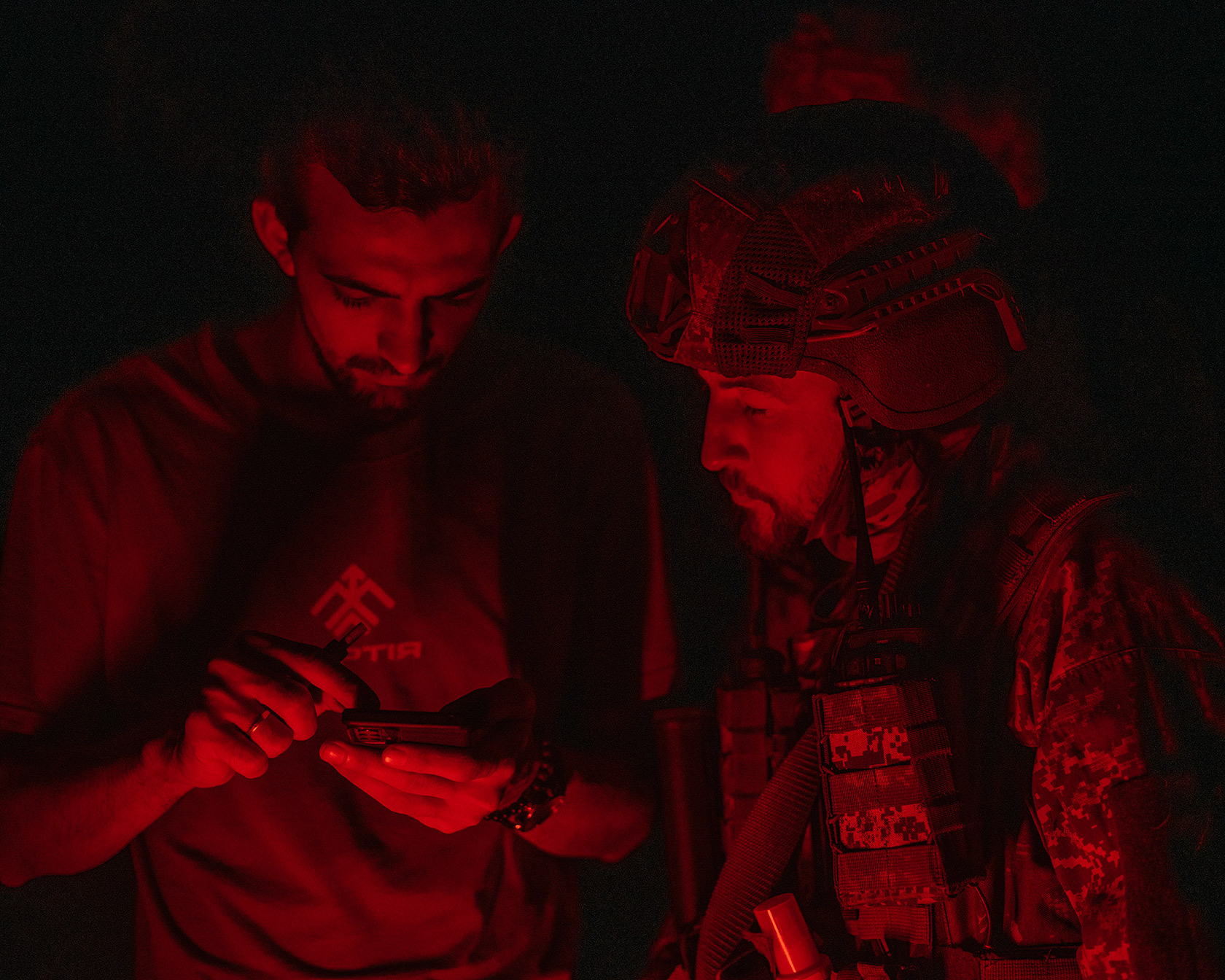

Two o’clock in the morning. Kharkiv Oblast, the Lyptsi front. The infantrymen, in full kit, gather at a pre-arranged location near an Oncilla armoured vehicle.

There are four fighters in the group: two making their first sortie and two more experienced. They all gather around the company’s senior sergeant, Volodymyr, who goes by the alias Single. He is carefully studying the screen of his phone.

"Note down the checkpoints," Single tells one of the experienced men, Shatai, who has already treated those injured on the battlefield and dragged out the fallen soldiers on his back.

Meanwhile, the driver asks Single whether he has given the group the drop-off point: from there the infantry will proceed on foot to their destination. Single nods affirmatively and turns to the newcomers:

"Keep your distance. Do whatever the guys say: if they say lie down – you lie down; if they say run – you run."

"Copy", replies one of the rookies, who goes by the alias Tykhyi (Quiet).

"Load your mags", Single continues. "Got your tourniquets? Got your first aid kit on the right side? If anything happens, Shatai knows what to do – he’s got the experience."

Suddenly, the silence is broken by a growing rumble. The driver advises us to step off the road. Seconds later, an Oncilla armoured vehicle roars past. A few minutes later, the guys will be boarding one just like it.

Single shows Shatai a map, asks if he remembers the landmarks and continues with the briefing. The soldier listens attentively.

"The first checkpoint is a hundred metres. Once you dismount – comms check", Single says, before giving the order: "Right, load up!"

One by one, the guys jump through the open doors of the armoured vehicle.

"We don't say goodbye", Single remarks.

"See you soon!" the soldiers reply.

The vehicle bumps along rough ground, jolting over potholes. The engine roars, the soldiers remain focused, travelling in silence, exchanging only a few words along the way.

"Guys, get out once I give a command!" the driver warns, and a minute later he shouts: "Get out!"

The soldiers leap out of the vehicle and vanish into the darkness.

Shatai

21:00, five hours before heading to the positions. Near the command and observation post, where operations are planned, we meet Shatai – one of those who will lead today’s group to the positions.

Shatai was born in the village of Khorosheve in Kharkiv Oblast. For a long time, he worked as a construction worker in Kharkiv. On 24 April 2025, representatives of the military enlistment office stopped him in his home village and took him to the district centre, Merefa. There he underwent medical examination and was declared fit for service. After that, he was taken to Kharkiv.

"The representatives of Khartiia arrived, which was good", he says. "And by 25 April, I was at the brigade’s base."

Shatai completed 60 days of basic combat training and two weeks of Khartiia-specific training. Today he is an assistant grenadier, having been deployed to the front for about a month. He has already completed two combat missions. The first took place roughly a week and a half after arriving in the combat zone. It went well.

"We set out at two in the morning, covering a long distance to deliver food and water to our brothers-in-arms on the positions, because the Vampire operators [the Russians] hadn’t made it in time", he recounts. "I walked with the senior officer – the one who knew the route – and memorised the way, noting where the cover was. We delivered the supplies and returned by eight in the morning."

As a young man, Shatai had served his conscripted term in a reconnaissance battalion, living in field conditions and undertaking long marches. Although twenty years have passed since then, he learned the basics of skills such as endurance during that time. Life and growing up in the village toughened him up and taught him how to navigate the terrain.

Therefore, during his second mission, Shatai, who already knew the route, led the group: there were four of them, tasked with rotating brothers-in-arms on the positions. However, the second time everything went awry: the soldiers walked into an ambush and failed to complete the mission.

"Probably a mortar had hit the area before [we arrived]. When we passed, a house was burning down, and immediately they started picking us apart," Shatai recalls. "One person was wounded. The medical training we had here helped, because I provided first aid – applied a tourniquet, packed the wound and stopped the bleeding – all instinctively. We saved the person’s arm, he didn’t bleed out, didn’t die. We got him into cover.

Another soldier in the group was killed in action. We went back for him over two days. When we retrieved the body, we set out at eight in the morning, moving in short sprints; we took a longer route. There were constant artillery strikes, FPV drones flying overhead. By eight in the evening, we delivered him."

Today, Shatai’s group is also set to go on rotation. They learned about the mission two days ago and have been preparing their kit, buying and gathering everything necessary.

"I will lead together with another person who has already walked this route", the soldier explains. "I walked a little further. He will take us along one route, and then I will take over. Today I will go at the back, and he will be the lead. Two people have not walked it yet. Small groups are the best option now: fewer losses, more concealment. We have two routes; we need a back-up option. We will be walking for about six hours. The faster, the better."

Shatai says that while a compass may prove useful once at the positions, on the way it is better to trust your own eyes, taking into account available cover and the ‘greenery’ to remain as inconspicuous as possible. You also need to keep "listening to the sky", which is "studded with drones", he says.

"The drones in the sky are never ours. If you hear a buzzing sound, it is better to stop, not to assume it is ours", Shatai advises. "An enemy drone can catch out the one leading us. And if it realises there is a group, an FPV [first-person-view drone] flies in or a mortar crew opens fire to cause chaos. Hide in the 'greenery' and let it hover above you. Let it pass, and then continue moving gradually.

We Ukrainians are fewer, and there are more of them [Russians]. Here you have to be crafty, dodge, think faster than they do, and hope in God – may He help."

Given that Shatai’s group successfully reaches its destination, they must hold the defence. They also need to set up decoys nearby to disorient the Russians – additional observation posts that are in fact empty. There is no set period for how long the troops will take up the positions. Despite this, Shatai is in a fighting frame of mind.

"You do not need to set off anxious. But you still feel something a little, because fearlessness is bad too. You must not relax, because this is responsibility, these are people, this is a rotation. Here we are like one team, like a family", he asserts.

"Motivation is home, your native Kharkiv, your oblast, so as not to let them [the Russians] within cannon shot. For now we just need to do this job, not let them through here as far as possible. And then time will tell", Shatai is confident.

Tykhyi ("Quiet")

22:00, four hours before departure. The soldiers are finishing their preparations.

Two newcomers are packing their things into open backpacks on the sofa under the watchful eye of the company’s chief sergeant, who goes by the alias Single. Bottles of water, sticks of sausage, blister packs of tablets, wet wipes and other essentials are peeking out.

The chief sergeant instructs the lads and, in a fatherly way, rearranges the items in the backpack of one of the newcomers, who is at least ten years older than him, including repacking bottles of water. "They pack their backpacks chaotically", Single complains. "And when a soldier puts on their gear, the 'weight distribution' kicks in and for the next five to seven kilometres the backpack presses on one shoulder. So the most important thing is correct weight distribution: start with the heaviest, then the lightest. The first kilometres are hard, after that you go all out."

Tykhyi, a grenade launcher operator who will set out at night on his first combat mission, listens intently to the sergeant.

"I arrived in the sector recently", the soldier tells us. "Then there was combat coordination, training at the locations. You make friends quickly here."

"Friends are in civilian life; here they are brothers-in-arms," Single corrects him. "And there are no friends left even in civilian life. This is the harsh truth of the modern world."

Single coordinates Tykhyi and the other soldiers, from receiving the combat task to taking up the positions. At the same time, instructors give guidance: on medical training, tactics and so on.

"In a couple of hours we assemble, get dressed – kit, backpack – and load into the vehicle, drive to the drop-off point and then get out and make our way to the positions", Tykhyi explains. "We have packed our rucksacks; they have everything needed for the first while. We have delivery by drones, and then we will be provided with everything we need."

Although today's sortie will be a baptism of fire, Tykhyi, like Shatai, is ready. At least, he assures us of this.

"I am confident in myself; I know what needs to be done. I am always calm, which is why my callsign is Tykhyi [tykhyi means both calm and quiet in Ukrainian]," he smiles. "Quiet and calm. The main thing is no panic."

We leave the soldiers so that they can get some rest before departure.

"The group consists of four people, you have seen three", says Single. "Riezia, the most experienced fighter, is sleeping. Let him sleep."

Single

23:00, three hours before departure. While the soldiers are resting before the mission, we return with Single to the command-and-observation post.

Volodymyr has been at war since March 2022, and in Khartiia since 2023. By the end of 2024 he was a senior rifleman. At the line of contact he primarily was involved in evacuation: pulling out the wounded and the killed.

"My group was located within a radius of 300-400 metres from the frontline positions," he tells us. "Everything flew at us: from 120s [120-mm mortar] to munitions dropped from drones. And we provided assistance quickly."

From June to December 2024, Single also performed the role of a guide – a person who knows the designated forested area inside out and can lead others to the positions. However, he says, last year "it was much easier to move": there was not the same density of Russian aircraft and FPV drones, especially the fibre-optic ones, as there is now in this sector.

"For a guide, the most important thing is memory and a cool head", he explains. "You must always remember the landmarks from one point to the next that you choose yourself. Even when you are walking at night, you remember them."

In February 2025, Volodymyr became the platoon signaller. For about the next two months he temporarily performed the duties of the company’s chief sergeant; recently he has fully taken on the role of chief sergeant. He also recently became one of the faces of the Grow in Khartiia campaign, whose examples of personal growth motivate people to join the corps.

"In Kharkiv and Poltava I’m on billboards. In Poltava I’m 'defending a gazebo'", Single says with a laugh.

The task of the company's chief sergeant is the training and supervision of the personnel. It all starts with selecting pairs: the company commander and he choose soldiers of roughly the same age, height and weight. Then they decide what work they will do together.

These pairs are then grouped into fours. They are given cohesion training. Finally, the soldiers are briefed on the combat sortie: who changes whom, which route they will take and in what order, where the checkpoints on the route will be, and so on.

"Under no circumstances will four newcomers deploy together; we always mix them up among themselves: one experienced, one new, one experienced, one new", Single explains. "The guide leads the new people and shows the way to the trio that follows him – they memorise the route. In this way we get three more people who know the paths they will need to walk in the future."

During preparation, Volodymyr tries to pass on his own experience to the soldiers: how to move, what to do when there is a strike and how to understand the direction of drone flights and projectiles.

"To understand whether a Mavic [a type of drone] is flying towards you or not, how a mortar shell flies, how an anti-tank grenade launcher flies", he continues. "If an experienced person hears the launch of a 120-mm mortar and realises it is not flying in our direction, they save time: they don’t take cover, they just keep going."

The situation on the front is dynamic. Soldiers must be ready for constant changes and unforeseen circumstances. For instance, the path used to exit a position may no longer be safe to re-enter, as the enemy may have taken control of it. Or a strike may have destroyed a tree that served as a landmark.

"That’s why we do everything online: people use gadgets to know the way", Single explains. "There’s always the human factor: sometimes you lose your bearings. We tell the guys: when you realise you’re lost, don’t be shy, call on the radio – we’ll always send a drone, find you and guide you to the right point."

At times, rotations are delayed. The main obstacle is enemy drones, which actively operate and monitor most of the paths used by troops. Single explains that soldiers are not withdrawn from the positions for long stretches for their own safety: "So that their movement in open spaces, their exposure to danger, and fatalities among them are all minimised."

The previous group that rotated off the frontline had been there for 84 days.

"I gave them all holidays, told them that if they didn’t go to the seaside, I’d hand them a reprimand", Single jokes. "You've spent two to three months at the frontline – you’ve got almost UAH 500,000 (about US$12,100) on your bank card, you have time to rest, spend at least a month recovering and continue your training courses."

Meanwhile, some of the fighters Shatai’s group was meant to relieve had already been at their positions for nearly 90 days. Once their comrades reached them, they were finally able to return to the battalion’s base.

But nothing went to plan: on their way to the positions, the replacement group came under fire. Mortars, artillery and drones hunted them.

Mobla

Three weeks later. Kryvyi Rih. Mobla, one of the fighters whose group was supposed to be replaced by Shatai’s men, is resting at home after coming off positions. He spent 99 days there.

"After such a long deployment, they gave us a holiday. Nobody bothers me here. Legally I have 15 days off. I can spend them peacefully at home or anywhere else", says the soldier, whose callsign comes from the video game Mobile Legends, which he enjoys playing.

Mobla is from Donetsk. He left the occupied city in 2017, having been unable to do so previously. Since then he has lived in Kryvyi Rih. He worked in a car service, specialising in restyling cars. In 2024 he decided to enlist.

"Maybe I dared to join the army because I had nearly lost my home, and I couldn’t return there", he says. "[The motivation was] to defend our land. And my wife. So that we are not slaves but free people. Most of my relatives turned away from me because I joined to serve for Ukraine, and they are on Russia’s side."

After training, Mobla joined Ukraine’s 54th Separate Mechanised Brigade, but "it didn’t suit" him. So he went absent without leave. Later he learnt about the chance to continue service in the National Guard without any consequences. And he "gladly joined Ukraine’s National Guard". Mobla has served in the Khartiia Brigade as a machine gunner for almost six months. His 99-day deployment became his longest.

"In winter, autumn, spring there are often mists or fog, so it's a week or two, a month at most, and then we rotate", Mobla explains. "But in summer it’s very difficult to rotate because of the weather. There was almost no rain or bad weather this summer. Of course, it’s war: if it doesn’t work out to rotate, then it doesn’t. If it does, we rotate."

Due to the large number of drones and guided aerial bombs used by the Russians against Ukrainian positions, soldiers must dig foxholes and stay in pairs. So if, for example, a guided bomb hits, it strikes a small group rather than a dozen people. Mobla adapted to the physical and everyday discomfort of such a "home".

"A foxhole is your second home. But you can’t sit there too long – you can go a bit mad", he says. "Physically, it’s better to move around, stretch your legs, because if you sit there too long, everything atrophies. We tried to move every 5-6 days: other positions had to be dug, someone needed help, sometimes a comrade came under fire and you had to run to save him."

"In everyday terms you understand you can’t go anywhere, you can’t just pop to the shop – that was fine for me. Of course, there are times when you can’t go out and use the toilet whenever you want. So you have to do it differently", he adds.

Even under such extreme conditions, fighters can go online and call their families to say the most important thing: "I’m alive, healthy, all good". They can also order "deliveries".

"We contact our guys, they go shopping and send things to us by drone", Mobla explains. "The drone may be busy dropping explosives on the Russians, or it may break down. We tried to order things that don’t go off quickly: sausage, processed cheese, pâté, bread, cigarettes and coffee. The guys also dropped us tinned food and porridge, and volunteers helped with supplies too."

At the start of August, Mobla and his comrades were waiting for rotation. Shatai’s group was just a kilometre away from their positions when suddenly they came under enemy fire.

An explosive dropped from an enemy Mavic drone hit right by Shatai’s left foot. The soldier saw a bright flash and realised he was wounded. For almost five hours he crawled back to the positions, disoriented, but a battalion drone helped him move in the right direction. At the position he waited nearly half a day for evacuation. Eventually, he was evacuated by a ground robotic system.

Now Shatai and other soldiers from his group are recovering from their injuries. This was already the second failed attempt to replace Mobla and his comrades.

"We waited for them to be withdrawn: it wasn’t an option to send in another group if there were still wounded left", he says.

"It wears you down mentally. Physically you know what to expect, but mentally you may not be ready for some things. There are drone drops and shells, all of it hits your head, and it piles up. They tried to rotate us twice: the first group came under fire, the second too – and somehow you lose heart a little, thinking that we’re going to be here for a long time. I kept myself going with the thought that my family is waiting for me at home, they love me, they worry."

The soldiers had to wait another ten days for the third attempt at rotation. Luckily this time the group reached them. On the evening of 12 August, Mobla and his comrades finally managed to leave their positions. They moved in pairs to pass the most dangerous stretch where there was no cover. They quickly returned to the battalion's base without any losses.

"We started moving after 18:00. And maybe stopped twice for five minutes – to smoke – the whole way", Mobla remembers. "That evening we probably heard five drones in total – and that's it. I don’t know, maybe we were lucky, but we got out very easily. We passed the most dangerous stretches so as not to expose the vehicles. Then a truck picked us up and drove us. By about 23:00 we were already at the base."

The first thing the soldier felt upon return was relief. He first cleaned himself up and then called his loved ones.

"On the way out some tried to cheer us up, saying we’d be home soon. Some swore", says Mobla. "When we arrived at the base, I realised I could finally rest from all those explosions. I called my family. My girlfriend burst into tears when she heard me and knew I was all right."

On 16 August, shortly after returning home, Mobla proposed to his girlfriend. She said "yes". Now the couple is waiting in line to register their marriage. But the soldier already calls her his wife.

A week of Mobla's holiday is over and another lies ahead. He tries to use this time as productively as possible, to be with his family and refocus.

"On leave I feel good. I eat well, I can always sleep", he says with a smile. "I don’t need to think about a drone flying overhead or going on radio duty. I rest with my family and try to let go of the war."

Even after 99 days in a foxhole, Mobla does not regret joining the army. And his motivation has not diminished.

"Many of our guys risk their lives to protect their wives and children. I’ve found many friends in the army. They've given me good advice too. My motivation hasn't changed at all, because the Russians aren't stopping. If we stop, who will defend us?

Author: Dmytro Kuzubov

Photos: Roman Pashkovskyi for the Khartiia Brigade

Translation: Myroslava Zavadska, Anastasiia Yankina, Anna Kybukevych

Editing: Shoël Stadlen