The Viktoriia Project: the story of the captivity and torture endured by journalist Viktoriia Roshchyna and thousands of Ukrainians imprisoned by Russia

This article is part of the international Viktoriia Project, launched by Forbidden Stories with the involvement of leading media outlets from around the world.

Forbidden Stories is a Paris-based international network of journalists that continues the work of journalists who have been killed, imprisoned or persecuted because of their professional activities.

After news of the death of Viktoriia Roshchyna broke on 10 October 2024, Forbidden Stories immediately launched the Viktoriia Project to carry forward her vital investigation.

Forbidden Stories undertook to investigate the circumstances of Viktoriia's captivity in Russia and to continue her work on the stories of Ukrainians held captive by Russia. Rough estimates suggest that more than 16,000 civilians are imprisoned in the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine and in the Russian Federation.

An in-depth examination of documents, testimonies and court materials has been ongoing for over six months. The investigation brought together 13 international media outlets, including Forbidden Stories, The Guardian, The Washington Post, Le Monde, Die Zeit, Der Spiegel, ZDF, Paper Trail Media, IStories, France 24, Ukrainska Pravda and Der Standard.

Our team of 45 journalists has conducted over 50 interviews with survivors of Russian imprisonment and those with firsthand knowledge of the system:

- 48 former captives who have revealed harrowing details of their detention and family members who have spoken about the fates of their loved ones;

- Four former prison guards willing to testify about conditions and practices within the prisons;

- Eight Russian human rights defenders who have provided expert comments on human rights violations.

This international investigation not only restores the voice of journalist Viktoriia Roshchyna, but also sheds light on one of the darkest chapters of the Russo-Ukrainian war, demanding justice and accountability for crimes committed against the civilian population.

#757

Volodymyr Roshchyn, who lives in the city of Kryvyi Rih in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, has been waiting for over a year and a half for his daughter Viktoriia to be released from Russian captivity.

Viktoriia, our colleague, a freelance journalist for Ukrainska Pravda and several other Ukrainian outlets, went missing in an occupied part of Ukraine in August 2023.

Since then, her father, along with lawyers, Ukrainian journalists and human rights defenders, has been trying to obtain at least some information about her whereabouts and the conditions of her detention. It was only in April 2024 that Russia officially confirmed that Viktoriia was being held captive.

The next letter from the Russians arrived on 10 October 2024, informing Viktoriia's family of her death, but providing no details or information about the circumstances surrounding it.

"It felt like a blow to me... It's difficult for me to talk about it," Volodymyr told journalists from our project team. "I didn't expect anything like this... Especially after we had been talking and preparing to welcome her back – and then this!"

Vika [diminutive for Viktoriia]. This photo was taken by Viktoriia herself in the city of Shchastia in Luhansk Oblast on 23 February 2022, one day before the full-scale invasion

In February this year, we met Volodymyr in Kryvyi Rih, at a shopping centre – the same place where he would meet Viktoriia whenever she passed through the city on her way between work trips to the front line.

"Not a single Russian institution has provided any information about what happened to Vika, where she is being held, whether the letter can be trusted, and if so, where the documents are that confirm her death and state the cause of death," he said. "All this time my family has been supporting me. We pray for Vika and believe that everything will turn out well."

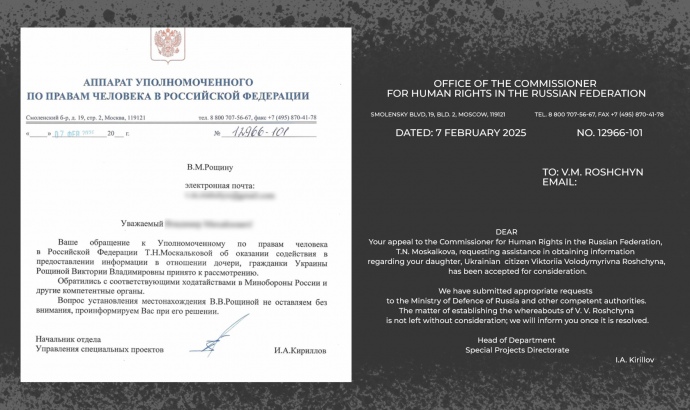

Volodymyr shows us a letter on his phone which he received on 8 February this year from the Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights in the Russian Federation, headed by Tatiana Moskalkova.

"The matter of establishing the whereabouts of V.V. Roshchyna is not left without consideration; we will inform you once it is resolved," the document reads.

On 14 February 2025, six days after Viktoriia's father received the letter from the Russian human rights commissioner, Moscow handed over the bodies of 757 fallen Ukrainian defenders to Kyiv.

Among them was body number 757, which was recorded in Russian documents as an "unidentified male" and bore only one unclear marking: СПАС (SPAS).

During an initial examination, pathologists determined that the body belonged to a woman. An investigation conducted by the Ukrainian Prosecutor General's Office has revealed a 99% DNA match with Roshchyna.

"The condition of the body and its mummification have made it impossible to establish the cause of death through forensic examination," Yurii Bielousov, Head of the War Department at the Prosecutor General's Office, told journalists.

Viktoriia's parents have requested an additional examination, as they have doubts about the reliability of the findings.

Bielousov stated that numerous signs of torture and cruel treatment have been found on Roshchyna's body, particularly abrasions and bruises on various parts and a broken rib. Experts also noted possible indications of electric shock having been used.

"The bodily injuries were inflicted while she was alive," Bielousov said. "Therefore, there is a high probability that she [Roshchyna – ed.] was tortured."

The investigative team conducting the inquiry told our project that the body had been brought back to Ukraine bearing signs of an autopsy performed in Russia. During the examination, it was discovered that several internal organs were missing: the brain, the eyeballs and part of the trachea.

An international forensic pathologist whom we consulted believes that the absence of these organs could have concealed evidence that death was caused by strangulation or suffocation.

As we have established, the abbreviation SPAS, which stands for "cumulative damage to the arteries of the heart" in Russian, may represent the "official cause of death" recorded by the Russian authorities.

The official investigation is ongoing. It may shed light on the conditions of Viktoriia's detention and help identify those responsible for her torture.

Together with our colleagues from other international media outlets, we have tried to determine the circumstances under which Viktoriia was captured, which prisons she was held in and for how long.

This is also a story about the hell and the ordeals that Ukrainian civilians have to endure in Russian-occupied territories and in Russian captivity.

VIKTORIIA'S PATH

Viktoriia made at least four trips to the occupied territories after the onset of the full-scale invasion.

She saw it as her mission and duty to report on the living conditions of Ukrainians under occupation. Viktoriia continued this work even after her first experience of captivity, when she was detained near Berdiansk in March 2022. During that time, officers from Russia's Federal Security Service (FSB) held her for 11 days and forced her to record a video renouncing any claims against the Russian authorities.

Even after her release, despite the pleas of her colleagues, Viktoriia continued her work in Russian-occupied areas. She reported on the sham "referendums" held in the occupied cities of Melitopol and Mariupol and spent 14 days with Ukrainians at the crossing point in Vasylivka, attempting to reach Ukrainian-controlled territory.

"Already during the war, she came home once and brought a battered helmet, body armour that must have weighed about 15 kg and her personal belongings," Volodymyr recalled. "Then she said, 'I'm leaving.' I said, 'Darling, stay' – this was after her first time in captivity. But she replied, 'I have to.' Well, how could I stop her? When she set her mind to something, she'd do it."

We have established that Viktoriia set off on her trip to the occupied territories on 24 July. During the night of 24-25 July, she crossed the border at the Uhryniv–Dolhobyczów crossing point in Ukraine's west.

Her journey then took her through Latvia into Russia via the Ludonka border crossing, from where she travelled to the city of Melitopol, which was occupied by Russian forces. There, Viktoriia planned to gather material about Ukrainians imprisoned by the Russians. She arrived in Melitopol on 26 July. The last time she contacted her editors at Ukrainska Pravda was on 28 July, without disclosing her exact location.

"As far as I know, Vika was staying in Enerhodar," her father said. "She'd found a flat there and was planning to live in it for a while. But then she went about her business. A witness [a woman who was in the same cell with her – ed.] said that just before she was detained, a drone flew over her. After that, a car came and took Vika away."

Viktoriia's former cellmate in Taganrog, Russia, said she had been held in Enerhodar at a police station located at 17 Budivelnykiv Avenue.

The Russians had set up a torture chamber at this location. We interviewed two other people who were also held at this address in 2022 and 2023. Both reported being severely beaten and subjected to electric shocks.

Serhii (name changed at the interviewee's request) ended up with a bag over his head inside the Enerhodar police station three times during two years of living under occupation.

He said the place was "supervised" by FSB officers – at least, that's how they introduced themselves during their first encounter. At the time, Serhii was accused of possessing weapons he had nothing to do with. During the next two arrests, he was not even informed of the reasons for his detention.

"They broke a PR-baton on me," Serhii recounted, describing a special rubber baton used by law enforcement. "It was the first time I'd ever seen one break. They broke my ribs. Split my head open with a rifle butt. Knocked my teeth out. It was awful – my back and arms were all black and blue. And the second time they took me, they used electric shocks. They called it 'a call to Putin' – they'd clip one peg to your ear and another to the little finger on the opposite hand, diagonally, then shock you. I don't even remember falling from the first jolt. The second time, they had to drag me out of the corner of the room."

It is likely that Viktoriia was subjected to the same method of electric torture. Her former cellmate recalled her mentioning that electric shocks had been applied to her ears.

"I know she was tortured with electric shocks more than once. She didn't say how many times, but she mentioned that her whole body was bruised."

In June 2023, Iryna Artiukhova, an employee of the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant (ZNPP), was subjected to electric torture at the Enerhodar police station. She was abducted from the garden of her own summer house and brought to the torture chamber. Eight men came to "arrest" her.

"They weren't soldiers; they were dressed in civilian clothes, but wore military body armour. They twisted my arms and wrapped my child's jumper around my head, blinding me so I couldn't see them," she said.

Once at the police station, it became clear that the Russians were not interested in Iryna herself but in her husband, Serhii Potynha, who also worked at the ZNPP. He had been engaged in volunteer work, delivering humanitarian aid to families with young children across Enerhodar. Iryna assumes that this was the reason the Russians targeted him.

Even though she was not their primary target, on the day of her detention she was beaten for a long time. After the beating, the Russians made a great show of "taking care" of her: they insisted she eat and gave her an ointment for her bruises.

"They poured water over me and connected electric shocks to make it hit harder through the water," Iryna recalled. "They clipped pegs onto my fingers, then hung them from my earlobes. They shocked me every time I said I didn't know where my husband was. They beat me with batons, shoved a pistol into my mouth, and ruptured my eardrum by slapping near my head. They hit my collarbone with a rifle butt, striking the same spot repeatedly. Later, when I was lying on the floor, they beat me with a cable. They said: 'The Chechens will come now, they'll rape you, they like girls like you'."

Sexual violence by FSB officers is not uncommon. Civilians who survived captivity have reported frequent threats of rape or being forced into same-sex acts.

Serhii recalled that during his first encounter with FSB officers they tried to force him to rape a fellow detainee after the latter had collapsed from beatings. When he refused, they continued beating both of them even more savagely.

"One time, they threw a boy into my cell, no older than 16-17," he recounted. "They tore his trousers off, threw him inside and shouted: 'F**k him!' I told them: 'Are you insane?' And they shouted back: 'Get on with it, you f**ker!' I refused. They beat us both and later took the boy away. It felt like they had some kind of fixation on this."

Both Serhii and Iryna eventually managed to flee the occupied city of Enerhodar.

But Serhii, whom the Russians ultimately managed to track down, is currently being held in Taganrog. Serhii was sentenced to 18 years in a penal colony on trumped-up charges by a Russian court in March this year.

TORTURE IN MELITOPOL

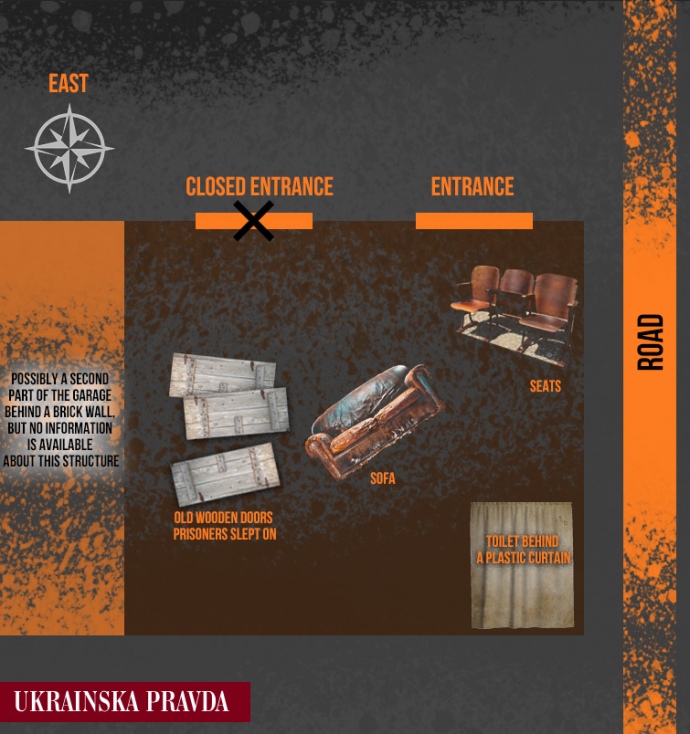

Viktoriia was transferred to occupied Melitopol after spending several days at the Enerhodar police station. We have established that Vika was most likely held "at the garages".

This refers to an unofficial prison and torture facility established by the Russians after the city's occupation. It consists of several buildings near a bus station in an industrial area of the city. Prior to the Russian invasion, various businesses operated there, including a grain elevator. The Russians have been bringing captured Ukrainians to this location since the spring of 2022.

We met with Vitalii (name changed at the interviewee's request) in the city of Zaporizhzhia in April this year.

He managed to escape from occupation in the autumn of 2022. However, before that, he spent several months in Russian captivity, including time at the so-called "garages". The Russians seized him one morning, directly from his workplace: a Toyota RAV4 and an UAZ Patriot pulled up to the location where Vitalii was working. He was forced to the ground, had a bag placed over his head and was immediately beaten.

It is most likely that they targeted him because he had travelled several times to visit relatives in Zaporizhzhia and later came back to Melitopol.

After searching his home, they took him to the garages in the industrial zone. As soon as Vitalii was brought inside, he was ordered to stand facing the wall. There were four other people there with him. For the next five minutes, he was beaten. The prisoners were forbidden to turn their heads or look around while this was going on. Eventually, the Russians left the prisoners alone.

"The other prisoners helped me wash the blood off," Vitalii said. "It turned out that there were people there who had been held for over 20 days. The garage wasn't small: ten by five metres, made of stone. There were two metal gates, and in the corner, behind a plastic curtain, was a bucket used as a toilet. Along the wall were chairs with foldable seats. On the floor, there were three or four old wooden doors covered with worn-out blankets. In the middle, there was an old sofa. That's where we slept."

He added that there were no windows. The prisoners could only guess the time of day by the light seeping through the cracks in the metal gates.

Soon, they came for Vitalii again. They blindfolded him and led him to another building for interrogation. He does not know how many people were present during the interrogation.

He said he heard only one voice. Vitalii was forced to lie on the floor, his hands and feet were tied. They began asking him questions: whether he knew anyone from the Security Service of Ukraine or the Armed Forces of Ukraine and what his assignment had been in Zaporizhzhia. Throughout the interrogation, he was punched and kicked. They connected wires and tortured him with electric shocks. Vitalii does not know how long it lasted. He remembers that after the torture he was unable to walk unaided – the Russians literally carried him back to the garage. The next morning, they took him to the local temporary detention facility, where he was held until September 2022.

The torture continued there. Vitalii recalled that the guards at the detention facility were not locals; they were Russian soldiers, likely from several different units. At first, the guards spoke Russian with a noticeable Caucasian accent. From August 2022, they were replaced by Russians who spoke without an accent.

He continued to be interrogated, as he described, "professionally, using physical force". Loud music played in the corridors of the detention facility from morning till evening: from the Russian national anthem to songs by the nationalist singer Oleg Gazmanov. Whenever someone was tortured in the neighbouring cells, they turned the music up even louder.

"They put Maksym Ivanov in the cell with me in September," Vitalii recalled. "He had been severely, savagely beaten. The Russians had captured him just before Independence Day: he and his girlfriend had been putting up posters around the city. One of the girls who was being held on the floor above was his girlfriend, Tetiana Beh. There was another girl, Liudmyla, but I don't know her full name."

The Russians released Vitalii at the end of September, forcing him to sign an agreement to cooperate with the FSB. A few days later, taking a huge risk, he fled from Melitopol to Zaporizhzhia.

Maksym Ivanov had also been held initially at the "garage" near the local bus station.

"They beat me with everything they could: first with their fists, then with rifle butts," Maksym recounted. "When they took me outside, I could feel them hitting me with all sorts of wooden sticks and metal rods. They put a bucket over my head. They started hammering on the bucket with something heavy – I could feel the pressure crushing down. I was already screaming, asking them to give me a phone so I could call my parents and say goodbye. They said: 'You're going to die, you scum, and no one will ever find out'."

He was held in a five-by-five-metre garage for four days. Together with four other men, he slept on sheets of plywood laid on the floor. The beatings continued throughout their detention. On the fifth day, Maksym, along with another prisoner, Vitalii, was transferred from the "garage" to the local temporary detention facility. It is located on the ground floor of the Melitopol District Police Department at 83 Hetmanska Street.

Maksym spent most of his time in the temporary detention facility alone in a cell. It was mentally exhausting, he recalled, as he could often hear the screams of other detainees being abused.

One day, Maksym was brought into an office and forced to write a letter to Vladimir Putin.

"I remember the heading: 'Moscow, Kremlin, to Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin, from Maksym Petrovych Ivanov', stating that I refused to accept Russian citizenship. I signed the refusal and they told me to expect that someone would come for me in the morning and that they would release me."

The next day, he was told to get ready. Maksym was driven towards Vasylivka. The Russians filmed him, making a show of reading out that he was being deported, and then ordered him to walk towards Ukrainian-controlled territory.

TAGANROG AND STARVATION

Our colleague Viktoriia Roshchyna remained in Melitopol until the end of 2023. At the beginning of 2024, she was transferred along with several other prisoners to Pre-trial Detention Centre No. 2 in Taganrog.

It was not until April 2024 that the official confirmation that Viktoriia was in captivity came from the Russians. However, they did not specify where she was being held.

Viktoriia's father contacted the International Committee of the Red Cross. They confirmed that Viktoriia was in captivity but reported having no access to her. Moscow had not brought any formal charges against her.

Human rights defenders refer to such prisoners as being held incommunicado – meaning that Russia holds them without official charges, they are denied the opportunity to correspond with their families, they cannot have a lawyer, and most importantly, such individuals remain invisible in official records.

"The official Russian penitentiary system does not even know itself how many civilian hostages it is holding, because a large number of the people are detained in unofficial torture chambers without any registration or transfer of information to official institutions. With incommunicado status, people held in torture chambers in the occupied territories or in Russia are left entirely on their own, completely unprotected from cruel treatment and torture, which not everyone is able to survive," said human rights defender Liudmyla Yankina.

In May last year, one of the witnesses interviewed by journalists from our project confirmed having seen Viktoriia at Pre-trial Detention Centre No. 2 in Taganrog. This place can be described as one of the most terrifying for Ukrainian prisoners. From the accounts of those who have been released, we know that neither lawyers nor international organisations such as the Red Cross or United Nations observers were allowed into this detention centre.

⚡️ A 3D model of Taganrog Detention Center #2 – where journalist Viktoriia Roshyna and other civilian hostages were held – recreated from dozens of interviews with Ukrainian former prisoners as part of the Viktoriia Project.

— Ukrainska Pravda in English (@pravda_eng) April 29, 2025

Full investigation into Roshchyna’s death and the… pic.twitter.com/Aqzg1j7jWB

For example, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Alice Jill Edwards, said in an interview with our project that she had attempted to visit prisons in the occupied territories of Ukraine and in the Russian Federation. However, each time the Russians denied her access.

"I wrote many letters. The only response I received was that visits to the occupied territories or to the Russian Federation to visit prisoners of war, as they say, are impossible. This is a rare occurrence among UN member states.

Many do not want the Special Rapporteur on Torture to show up on their doorstep. Once my visit is accepted, I have the right to make unannounced visits anywhere on the territory. So it is a risky step for countries that have something to hide. But refusal is part of the torture machine, if you will," Edwards said.

She also added that torture has become an institutionalised practice both within Russia and beyond its borders.

What happens behind the walls of Russian prisons can only be learned from the testimonies of those whom Ukraine has managed to bring home.

Prisoners held in Taganrog are completely isolated from the outside world – they have no right to visits, parcels or letters. The Russians use dozens of types and forms of torture methods, ranging from the beating of prisoners during the so-called "reception" (when Ukrainians are first brought to the pre-trial detention centre and dragged out of prison vans) to torture by starvation and the constant sound of people being beaten in neighbouring cells.

Viktoriia ended up in this place.

"A witness (who saw Viktoriia in Taganrog) told me they were fed on rotten potatoes there," Roshchyna's father told journalists in an interview. "The witness couldn't eat the food for the first three months because it was inedible. But later, she started eating anything just to survive. Vika couldn't eat it either. Due to malnutrition, she began losing weight rapidly. The witness said that at one point, the guards forced Vika to eat."

He believes that Viktoriia did this deliberately – to force the Russians either to release her or to transfer her from the pre-trial detention centre to a hospital where she could receive assistance.

Vika's former cellmate said that in the summer of 2024, the journalist was eventually taken to hospital because she had become so weak that she could barely walk unaided. Later, her father learned that armed guards had been assigned to Viktoriia's hospital room.

How exactly she was treated and what diagnoses were made remains unknown. After spending several weeks in hospital, Viktoriia was brought back to the Taganrog pre-trial detention centre. This time, however, she was placed in solitary confinement, separated from the other prisoners.

"A doctor came and examined her and then she was taken to hospital, but it was unclear where. She returned with a 'butterfly' cannula on her arm; they had put her on an IV and forced her to eat," recounted another witness from the Taganrog detention centre whom our project team was able to interview.

The witness added that at some point, the prison staff even began preparing separate meals for Viktoriia, asking the other women what she was eating.

Viktoriia's father recalled that in August he spoke to his daughter by phone. Representatives of Ukraine's Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War had asked him to try to persuade Viktoriia to end her hunger strike.

"I said: 'Darling, you need to eat, they’ve promised to release you'. And she replied: 'Yes, I'm eating, I swear'. Vika was the kind of person who, if she said she would do something, she would definitely do it," Roshchyna's father told journalists.

Sources in Ukrainian intelligence and among Russian negotiators involved in prisoner exchanges noted that Viktoriia had been due to be swapped in September 2024. But the exchange never took place.

The reasons why this did not happen remain unknown. We do know that on 8 September, Roshchyna was taken out of her cell and prepared for a long journey back to Ukraine. A prisoner in Taganrog we were able to interview was among the last people to see her alive.

"We asked a girl from a neighbouring cell to help her down the stairs," the witness said. "With her help, she managed to get down. Afterwards, a guard came and said that the journalist had not made it to the exchange. He added: 'It's her own fault'."

Our sources in Ukrainian intelligence reported as early as October last year that Viktoriia had died while being convoyed.

Roshchyna's story is not an isolated case. Most of the Ukrainians held in Taganrog's pre-trial detention centre are military personnel. However, the Russians are also holding a number of Ukrainian civilians there. The conditions of detention are the same for both categories of prisoners.

Yelyzaveta, a former Ukrainian soldier who was a civilian at the time of the full-scale invasion, spent a year and eight months in various prisons in Russia, including Taganrog.

She had attempted to leave occupied Luhansk Oblast but was stopped by the Russians at a checkpoint and sent to a filtration camp, then transferred to Pre-trial Detention Centre No. 2 in Taganrog – supposedly for not disclosing her prior service in the Ukrainian military.

During her "reception", she was stripped naked and filmed from all angles before being issued clothing: a nightdress resembling a floor rag, underwear with visible signs of previous use, trousers several sizes too small and an oversized hat and jacket.

"Get ready, we'll show you all the delights of life," the detention centre staff told her.

Yelyzaveta was then led down a corridor, her arms twisted so that she could only see her feet. Along the way, she was beaten with sticks and metal rods, and dogs were set on her. Some men shouted: "They've brought us another Ukrainian whore, we're going to f**k her."

Eventually, Yelyzaveta was thrown into a cell: barred windows, three-tiered bunks, a thin mattress, but no pillows or sheets. A metal bench and table were bolted to the floor. There was a toilet and a washbasin. Every time the food hatch in the door was opened, she was forced to stand facing the wall with her hands behind her back and shout: "Good morning, citizen chief."

"The food was terrible. The bread was inedible: if you threw it at the wall, it could stick to it," Yelyzaveta said, describing the food brought by detention centre staff. "It reeked of raw dough. If it was soup, there would always be curly hairs and snot floating in it. There’d be dirt or sand at the bottom of the bowl. There were bits of unwashed onions chopped up, unpeeled beetroot cut together with the tops. Sometimes there was a potato – unpeeled and sprouting. They called this borscht."

There was no drinking water – only tap water that had a greenish tint and smelled of fish. There was no soap in the cell, just a small rag that the prisoners used to wash the dishes.

Bohdan, a soldier from the Azov Brigade who was captured by the Russians, was taken to Taganrog in September 2022 and spent around six months there.

He was held in two parts of the pre-trial detention centre: the old building and a newly renovated one. The facility had nine guard posts, each responsible for overseeing 15 to 16 cells.

Women were held at the last post, while the sixth post housed the punishment cells. According to Bohdan, those sent there were often accused of absurd crimes – for instance, Ukrainian tank crew members whom the Russians claimed had attacked the Mariupol drama theatre.

Bohdan said they were given very little food – just 200-300 g per person each day. The military detainees estimated this to be about four and a half spoonfuls. Lunch might consist of cabbage water with a few shreds of cabbage, and dinner of plain pasta or millet. Occasionally they were served fish mixed with entrails and bones.

He also recalled that civilians, particularly residents of Kherson Oblast, were held in Taganrog, though he did not know how many.

The torture of both military and civilian prisoners in Russia and the occupied territories is systemic and extends far beyond Taganrog.

It is now clear that the Russians had been preparing to receive prisoners, and that the torture was not the result of individual excesses – it was part of state policy.

HOW THE SYSTEM PREPARED TO RECEIVE PRISONERS

Russia has a long history of using its repressive system to persecute pro-Ukrainian citizens.

As early as 2014, the occupying authorities were persecuting people in Crimea, extracting confessions through torture.

One such example is the story of the Sentsov group – activists whom the Russians accused of planning terrorist attacks on the peninsula.

In spring 2014, the Russians detained Oleg Sentsov, Oleksandr Kolchenko, Oleksii Chirnii and Hennadii Afanasiev.

Afanasiev was tortured and coerced into signing a confession saying he was a member of a terrorist organisation. He did sign the confession, but during his trial in Rostov in July 2015, he stated that the confession had been made under torture and that all of his testimony was fabricated. Sentsov also reported being tortured.

After his release from captivity in 2019, Kolchenko told Ukrainian journalists that at the time of their arrest, the members of the so-called Sentsov group barely knew each other.

They didn't even know each other's full names – yet this did not prevent Russian investigators from branding them a terrorist organisation. This experience was later used to justify the continued persecution of pro-Ukrainian citizens in the occupied territories. By the end of 2021, around 200 people were being held in Russian captivity.

Another telling example of Russian torture is what has become the most notorious secret prison in occupied Donetsk Oblast – Izolyatsia (Isolation). The Russians took control of this former arts centre in June 2014 and repurposed it as a prison, where Ukrainian citizens were subjected to torture.

Ukrainian activist Liudmyla Huseinova was captured by the Russians in 2019. Prior to her abduction, she worked at a poultry farm in Novoazovsk, Donetsk Oblast, and cared for orphans in Prymorsk, Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Due to her outspoken pro-Ukrainian views, she was seized and sent to Izolyatsia, where she was held for approximately 50 days.

Huseinova says that she cannot remember part of what happened to her in Izolyatsia. However, she does recall what she was fed.

"For some reason they decided that I was on a hunger strike," Huseinova said. "And they forced me to eat on camera, bringing in special meals: they overcooked pearl barley with rubbish, dirt, possibly traces of mice and stones."

Conditions at the Donetsk pre-trial detention centre were equally dire. Prisoners were given filthy, foul-smelling fish, boiled without being cleaned. Desperate from hunger, the women held with Huseinova would wash the fish with water, mix it with bread and secretly boil it in a metal bowl using an immersion heater, seasoning it with sunflower oil.

"Those who had AIDS or tuberculosis were at an advantage: once a week, they were given a boiled egg and perhaps 100 g of cheese," Huseinova recalled. "It seemed strange to me, but many dreamed of contracting tuberculosis just to be transferred to another floor, where the food was better."

Liudmyla Huseinova

Our project's partners managed to speak with several former employees of the penitentiary system who had left the territory of the Russian Federation. On condition of anonymity, they agreed to reveal how Russia prepared its prisons for the reception of Ukrainian prisoners following the start of the full-scale invasion.

For example, a former officer from the Federal Penitentiary Service (FSIN, by its Russian abbreviation) described how, in the spring of 2022, special police units began to be sent on "rotations". At first he thought they were being deployed to the war. However, it turned out they were being sent to torture prisoners.

"It wasn't only about military personnel – only a small percentage were soldiers," the Russian said. "The rest were civilians. These were people who had been abducted, taken to Russia and subjected to horrific treatment."

One such unit, named Zubr, was deployed to the town of Novozybkov in Bryansk Oblast, Russia. His unit also underwent several rotations across various prisons within Russia. Our interviewee’s account is supported by documents provided to us by Ukrainian intelligence.

The documents reveal that Russian special units from the FSIN were assigned to guard facilities where Ukrainian prisoners – both civilians and military personnel – were held. These units rotated periodically, with several prisoners interviewed for this project noting that the guards changed approximately once a month.

Units with the same names could be encountered in several locations. For example, the activities of the Grozny unit (Chechen Republic, city of Grozny, headed by Apti Turayevich Azhiev) were recorded not only in Taganrog, where Viktoriia was held, but also at Pre-trial Detention Centre No. 2 in Borisoglebsk, Penal Colony No. 9 in Borisoglebsk, Penal Colony No. 12 in Kamensk-Shakhtinsky, Pre-trial Detention Centre No. 2 in Kamyshin, Pre-trial Detention Centre No. 2 in Novozybkov, Pre-trial Detention Centre No. 2 in Kineshma, and Penal Colony No. 120 in Volnovakha (Ukraine), which is currently occupied.

Members of this and other units were involved in the torture of Ukrainian military and civilian prisoners. According to the former FSIN officer, it seems that these special units were explicitly given orders to carry out such actions.

"Before our unit was sent on 'rotation', General Igor Potapenko addressed us," he recounted. "He gathered those who were going on assignment and ordered them to work thoroughly and harshly. The message was simple: 'Do your job well – and no one will ask any questions'."

Later, during a meeting with commanders, the situation became clearer: the special units were informed that in the prisons they were being sent to, there would be no oversight or surveillance cameras.

The heads of the units were explicitly told, "Do whatever you want." Our interviewee recalled that a sense of impunity began to spread. When special units returned from their assignments, they could not understand why they had been allowed to torture prisoners with electric shocks in the showers there, yet were forbidden to do the same at their home bases. Some individuals who did not want to take part in such activities chose to resign.

Another senior official from the FSIN system revealed that special units from the Penitentiary Service beat prisoners under the instructions of supervisors from the FSB. Speaking on condition of anonymity, he explained that interrogations were not organised by the main FSIN directorate, but by "colleagues" from another agency.

To oversee such operations, staff from the Main Directorate of the Federal Penitentiary Service were sent to the prisons where Ukrainian prisoners were being held – not only within Russian territory, but also in the occupied territories of Ukraine.

"The primary goal was to obtain any operational data that could be used, primarily for military purposes," the source said. "Intelligence on facilities, training locations, names of commanders and individuals who might have connections. Even the names of civilians who could be of interest.

The FSIN employees responsible for contact with prisoners had no idea what to do with them. They didn't know how to act, and in many cases still do not. As a result, they resorted to torture.

But in any case, the overall leadership was exercised by the FSB – interrogations and the control of prisoners of war are not the primary function of the FSIN," they added.

They also added that the FSB is always present and oversees the actions of FSIN employees, operational units and other personnel.

These words are indirectly confirmed by some of the prisoners we have interviewed. They recalled encountering individuals who were different from the usual officers of Russia's National Guard or FSIN, and who directly proposed cooperation with the Russian Federation.

In addition, as the FSIN system source stated, the FSB oversaw such operations remotely from Moscow. Those working in the Russian capital would occasionally travel to the Lubyanka, the FSB's headquarters, to receive new instructions.

"This was discussed frequently, particularly during smoke breaks," the source recalled. "They would share all sorts of stories: accounts of prisoners, torture, even stories of how 'our guys cut someone's balls off'. Such conversations were constant. I believe much of this wasn’t directly ordered – it was the influence of propaganda, in an environment where cruelty had become the norm."

If we analyse the data from 29 pre-trial detention centres and penal colonies where torture has been confirmed by at least two sources, we can state with certainty that prisoners were beaten in each of them. Furthermore, in nearly all of these facilities, prisoners were subjected to electric shocks.

In about two-thirds of these prisons, there have been documented cases of suffocation, sexual violence, torture with fire and various forms of physical exhaustion. This is only a part of the extensive list of torture methods devised by FSIN personnel.

We know that our fellow journalist Dmytro Khyliuk has been attacked by service dogs and subjected to starvation torture while detained in a penal colony in the settlement of Pakino in Russia's Vladimir Oblast.

Moreover, when an outbreak of scabies spread among the prisoners, they were denied treatment. They were forced to sing the Russian national anthem and memorise Russian songs, and beaten if they refused. Ukrainians were also forced to burn or scrape off their tattoos using stones.

In Pakino, prisoners were prohibited from sitting or lying on the bunks during the day and were forced to stand for hours, leading to severe swelling in their legs. Threats of rape and execution were frequent. In some prisons, those who could not endure these conditions died; we are aware of dozens of such cases.

At least 15 Ukrainian citizens have died as a result of torture and the harsh conditions in Pre-trial Detention Centre No. 2 in Taganrog alone, where our colleague Viktoriia Roshchyna was held.

***

Unfortunately, the scope of this material, like that of others, does not allow us to describe each of these penal colonies in detail.

As of April 2025, we are aware of 186 detention sites where Ukrainian citizens are being held. Torture is carried out regularly in at least 29 of them, as confirmed by both a UN report and a report from Ukrainian intelligence, both of which our project has access to. However, this list is not exhaustive.

In the second part of our report, learn about how Russia created a prison system designed for torturing captives and exactly who is involved in the torture of Ukrainians.

Authors: Stas Kozliuk, Sevgil Musaieva, Anastasiia Horpinchenko, Ukrainska Pravda

Translators: Anastasiia Yankina

Editor: Artem Yakymyshyn