Coming home: why Ukrainian refugees are coming back from Germany

Iryna Fingerova is a writer and doctor from Odesa, currently based in Dresden. She has lived in Germany since 2018.

In January, she wrote about her experience of treating Ukrainian refugees.

Now she shares the stories of elderly Ukrainian women who fled to Dresden from the full-scale war, and others who stayed in Odesa despite Russia’s deadly missile and rocket strikes.

Some are patients of hers, and some are regulars at the Ukrainian House in Dresden whom she interviewed.

These are stories of people counting the days until they can go back to Ukraine, and people who are trying to start a new life in an unfamiliar city in their seventies and eighties.

These stories tell of tough decisions, a yearning for home that’s stronger than fear, and the right to die in one’s own home – or find joy away from it.

***

I saw Ms L. on Friday.

"It’s no good at all," she said without even taking a seat. "There’s sickness everywhere, even in his bones. They say there’s nothing they can do."

Her husband started radiotherapy at the university hospital’s oncology department a few days ago. He has gallbladder cancer. The couple came to Dresden from Lutsk, northwestern Ukraine, just over a year ago.

"It would make sense to arrange for palliative care," I venture.

"We’re going back tomorrow! I came to say goodbye."

We agreed that I would write a prescription for a walking frame and some strong painkillers.

"It’ll be easier for you if you stay here, but easier for him if you go," I told her.

We sat there in silence.

"It won’t be easy for me either way. At least it’s better to die in your own home," Ms L. said.

I agree with her.

What could be worse than not having control over that final decision?

Over the past year, I’ve seen many people struggling to accept this loss of control. The war strips away all pretence that we have some sort of control over life or death.

At home, all these people were used to having a plan, or if they didn’t have one, to hustling, constantly adjusting to the world around them. But in Germany they were afraid of making any misstep, so they chose to stand still.

They were all suffering from having had their right to choose where and how they wanted to live – and sometimes to die – stripped away.

They were suffering from not having a choice.

But in the end, all of them did make choices.

They didn’t choose the circumstances they ended up in, but they could choose how to adapt to them and what to do next.

Or what not to do next.

To stay or to leave.

To go back to Ukraine.

To be afraid or to stop being afraid.

To wait for life to start again, or to live.

None of those choices were easy – not for the kids, not for the adults, not for the elderly people.

What is it like leaving your homeland not to live, but to die? Or staying behind when everyone else leaves?

It depends on the choices you make.

Ukraine's black soil instead of Oxycodone

Ms Ch. came from Kharkiv. Her house was hit by a missile. A piece of debris lodged itself in her spine, paralysing both of her legs. Another one injured her stomach: she has had part of her small intestine removed and a stoma made in the front of her abdomen.

When I first saw her discharge summary, I felt unwell. When I saw her 10 minutes ago in the hallway, I saw a friendly, smiling woman in a wheelchair – aged 50, no chronic conditions, a former nurse, with her husband by her side.

Ms Ch. underwent surgery in Kharkiv, then in Lviv. She came to Germany for rehabilitation, spending four months in a hospital not far from Dresden. The list of drugs she was taking was two pages long – a ton of psychopharmaceuticals, sleeping pills, antidepressants, antipsychotics, tranquillisers, painkillers, painkillers, painkillers.

She wrote to German professors using GoogleTranslate, she scoured every corner of the internet looking for prescriptions and referrals for everything there was: occupational therapy, physiotherapy, gymnastics. Maybe another consultation with a neurosurgeon? No, no opiates, no opiates, I don’t want to be addicted, I’m a young woman!

Sometimes she had no strength left to fight. On those days, I would just take her blood pressure and write prescriptions. Other days, her eyes would glimmer with hope, and we’d think about where else we could turn to for treatment: what might make sense, and what her insurance would cover. Because where would she get that sort of money from? When you’ve spent your whole life saving for home renovations, it’s hard to put money aside for an appointment with a neurosurgeon.

Last time I saw her, Ms Ch. had found a pain clinic. I wrote a referral for her and contacted the clinic, and she was admitted.

Over the course of four weeks, doctors tried everything they could to help her. We got a letter saying they’d cancelled half of her antidepressant prescriptions but got her on high doses of Oxycodone, a powerful opioid. But what about her fear of getting addicted?

I called Ms Ch. to ask her if she accepted the doctors’ decision.

"Hello!" she said. "What good timing. We’re leaving tomorrow."

"Where are you going?" I asked.

"Back to Kharkiv. We’ve arranged for a bus and an ambulance to take us."

"What will you do there?"

"Same old same old! Physiotherapy, pills. I’ll keep living! But I’ll be among people I know. We can’t go back to our apartment yet, so we’ll stay with relatives. I just can’t stay here! Everything takes so long! No one gets me. I stopped taking those drugs three days ago. We know a doctor in Kharkiv, my husband got in touch with her."

"Good luck," I said. "Are you sure?"

"Yes. I cried and cried, and now I can finally breathe again."

Six different doctors had diagnosed Ms Ch. with post-traumatic stress disorder, she was taking a ton of drugs to help with her panic attacks, and now she’s travelling back to the site of her trauma.

Because the longing for home can be stronger than fear.

Hika, who refused to die

I called her Hika. The nurses at my hospital called her Frau H.

She was 85 and a refugee from Ukraine. She had lived with her family in Mykolaiv for the past 25 years, but she had a Georgian passport, which made it difficult for her to access benefits in Germany.

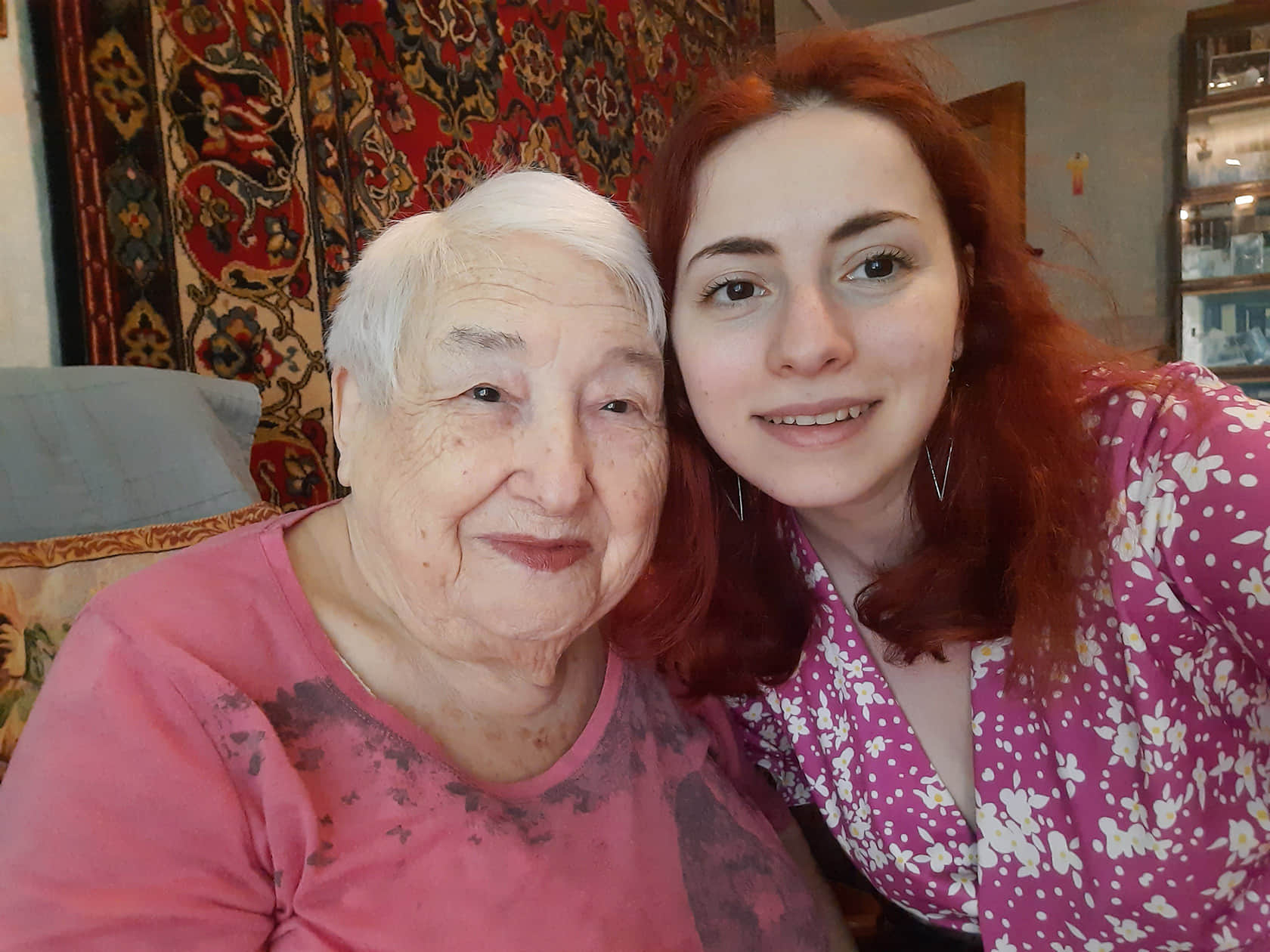

The first time I saw her, she came with her granddaughter, a slender young woman no more than 20 years old.

Hika could barely stand. She’d been hospitalised two weeks before with a sharp pain in her chest. A cardiogram showed she’d had a heart attack. She had bypass surgery and was given blood thinners and sent home. Within a week she was suffering from shortness of breath, bad enough to call an ambulance. The doctors found she had an embolism; her pulmonary artery was blocked.

A couple of days later she was stable again. She was discharged and referred to a family doctor to get a prescription for the medications she needed.

"The pain is awful!" Hika said. "Just give me something, dear child!"

She was taking opioids and analgesics three times a day. I didn’t change her prescription: I just prescribed analgesic drops rather than tablets. I felt she would trust the drops more.

"Exactly 36 drops twice a day and your pain will be gone!" I told her.

"Dear child, I’m dying, it’s obvious. Can you please tell me it’s okay for me to fly? I want to die at home!"

I told her she should come back in a week and cancelled her opioid prescription. She wasn’t taking them anyway. In fact, she wasn’t taking anything she was prescribed. She told me that when her granddaughter left the room to go to the toilet.

"There are 100 pills in a pack," Hika told me. "I’m not stupid. The doctor told me to take them for six months, but you only prescribed enough for three months."

"But it’s free. I can only prescribe one pack at a time, but you can come back in three months and I’ll renew the prescription," I replied.

"But I’ll be in Georgia! And they’re expensive! Why would I start if I won’t be able to take a full course?"

"Here we go again!" the granddaughter burst out. "You can’t go anywhere!"

"I won’t take the pills then!" Hika said, dramatically crossing her arms in front of her chest.

I offered a compromise.

Hika would stay for another three months, then fly home after renewing her prescription and obtaining the medicine. That was what we agreed: I trusted her word, I trusted that she really needed to go back home, that she’d be better off that way. And she trusted me when I said she needed to take blood thinners for at least six months. I took her seriously, and she agreed not to die of an embolism.

"You really think it’s a good idea?" Hika’s granddaughter asked me.

"Of course," I replied, "everyone has the right to die at home. But she doesn’t want to go there to die. Whereas here, she would have died."

Hika never came to my surgery again.

A dress from Kharkiv

The next day, I saw Tetiana. She was suffering from nausea after having her gastritis treated.

"I don’t know if it’s the pills you prescribed that make me feel sick or being in Germany," Tetiana said.

"We’ll try Pantoprazole," I replied. "You’re not planning to go back, are you?"

"Why not? I need to go! All my clothes are there. I want my dresses back. Here I always look frumpy, but in Kharkiv I headed an HR department!"

Tetiana is 85. She suffers from hypertension and constant dizziness. She has osteoarthritis in her left knee and her right shoulder. I could hardly imagine her making the long bus journey back to Ukraine.

I did still write her a prescription for compression socks, just in case – to help with her varicose veins and the possible 48-hour journey.

As Tetiana was leaving, I asked her: "Do you have any friends?"

She laughed. "Friends, at my age!"

I said she should go to a weekly meeting for older people held at the Ukrainian House in Dresden, and gave her the phone number for Vlada, our wonderful psychotherapist.

"Every Wednesday. There’s tea, sweets, and good conversation." I was so eager to convince her the meetings were worth her time, I sounded like a professional saleswoman.

About a month later, I went to the Ukrainian House to interview people for Gemeinsam Heimatlos, a project comprising a series of interviews and photographs of refugees from different countries.

Tetiana was there.

She was wearing a beautiful blue dress.

"It’s from Kharkiv," she whispered in my ear as I was reaching for a biscuit. "I went home to get my clothes and came back. I got to see my friends, smartened myself up a bit. Isn’t that nice?"

I swallowed the biscuit, turned on my dictaphone, and started asking the people who came to the club about their lives.

The two stories below are told in their own words.

Tetiana Oleksandrivna, who misses her tomato plants

"I’m from Kakhovka. I’m 71 – almost 72.

I wasn’t going to leave Ukraine, but my son said I had to. He left Kharkiv in the early hours of 24 February 2022. He has three kids.

I stayed behind. My husband died a long time ago. I was scared of leaving, but staying was even scarier. Everything was shaking, and the ground trembled. My son said to me: ‘Mum, you’re on your own, you’ve got no one there. To hell with the garden and the house – the most important thing is that you don’t die!’

My son and his family had settled in Dresden, so I joined them.

Leaving was hard. My neighbour was driving his daughter; they brought me along with them. It took so long to get to Kherson… There were wrecked tanks on both sides of the road, checkpoints everywhere. We spent a night in a hospice – no, a hostel – in Khmelnytskyi, and next morning we carried on driving… It was tough!

I like Dresden. There’s lots of places to go to. We didn’t have a lot of choice in Kakhovka, just the community arts centre really. Though we did have Nova Kakhovka nearby… It’s so beautiful there!

Our dam was blown up on 6 June or around then. On the 7th there was a meeting here. We wailed, and cried, and hugged each other. Such a terrible disaster! Everyone I know is still there – friends, relatives – it was just 10 km away from us. What happened to people who couldn’t walk? I gave my friends the keys to my house so they could wait it out there. They said it was a scary time, there was a lot of looting – people just took everything they could carry. I worried for the young girls…

How can I live with all this? My grandchildren are my only source of solace. At first we all lived together, but now I have my own place.

I felt like I didn’t belong here! Until I met the ladies from the Ukrainian House. Now I have friends, my wonderful girls: Zina, Oksana from Kyiv – she’s over there crying, she’s a crybaby like me – Marysia, Zhenia from Kharkiv, Lienochka, aged 86, from Kyiv – she’s got a wonderful singing voice…

I’ve started learning German, because I realise I’ve got nowhere to go back to. There are no hospitals and no pension fund there.

Here, I’m trying to live. I’ve got flowers everywhere, but I can’t grow tomatoes here. You should have seen the tomatoes I grew in Kakhovka! I miss them like they’re family. I wanted to plant something in the courtyard of my building here, but it’s not allowed. You need special permission.

The people here are strangers, but they treat us with understanding. Once I went to a shop to get some vegetables – it’s run by Vietnamese people, and they sell clothes, bags and shoes as well. I heard that you could get trousers taken up there too.

I asked the woman working there: ‘Wie viel, Hosen?’, gesturing with my fingers as if cutting with scissors: how much does it cost to hem a pair of trousers?

She said: ‘Zehn Euro.’

Ten euros! That’s expensive! I’d turned around to leave, and she asked me: ‘Russisch – Ukrainisch?’

I said: ‘Ukrainisch.’

She said: ‘Five euros, then!’

I was so moved that I hugged her, and started crying.

What else can you do when people are so kind?"

Zinaida Serhiivna, who made Molotov cocktails

"I’m from Zaporizhzhia. I came with my granddaughter and my great-granddaughter. We left after they started attacking Enerhodar. We got here on 6 March 2022.

I’m 77. I’m a civil engineer, but I worked in sales and procurement.

I retired when I turned 56, but I wasn’t one for sitting at home. I was fascinated by medicine. I completed a training course, learning how to do massage, bandage wounds, and give injections. I was good at it. I was bored at home, so I worked as a nurse until I was 76. My first patient was a man who’d fought in Afghanistan – he was bedridden, and I got him into a wheelchair. I loved all my patients like family. I raised both my grandchildren as well.

My grandson is serving in the military, he’s a conscript. He was due to finish his military service, but the [full-scale] war started – it’s his third year in the army now. I only see him when we call on Viber. We talk every morning and every night. He sends at least a brief message. This child that I raised… It’s heartbreaking… He’s in trenches somewhere, in a forest. I help him out with money. I send him money and parcels. You know, some of those guys are orphans, so I send them warm clothes, some food, medicine…

Our decision to leave was sudden. I hadn’t been planning to go. I was born in Zaporizhzhia, my home is there. And we had things to do! I’m the deputy head of our building’s residents’ association.

I had keys to the storage room and the janitor’s room. One of my neighbours, a young woman – her boyfriend joined the territorial defence, so we let them store canisters there. They taught us how to make [Molotov] cocktails. We pretty much did it round the clock, in shifts, and were always in a rush. I used to bake pasties for the boys as well.

I wasn’t planning on going anywhere, but my granddaughter – she’s a hairdresser – came to cut the boys’ hair one day. She saw soldiers, and she just felt scared. Her hands were shaking as she was cutting their hair. One of them said to her, with a very serious expression on his face: ‘Leave the city if you can, sweetheart. It’s going to be hot here.’ She told him: ‘My grandma doesn’t want to go.’ And he replied: ‘There’s no men in your family, it’s just you, your daughter, and your grandma. If they [the Russians] take the city…’

After that, we left.

We thought we’d be away for a week or two… we hardly brought anything with us.

My granddaughter brought her hairdressing tools and her laptop. I brought a loaf of our Zaporizhzhian bread, a kilo of nuts, three chocolate bars, some water, and my cat in his carrier. My great-granddaughter brought some drawings and her tablet. She’s very creative.

It was quite a journey: 18 people squeezed into one compartment on the train to Lviv, then a minibus, then crossing the border by foot, and then travelling on to Dresden.

The journey took two days. We barely slept. A German man took us in, a friend of my granddaughter’s client’s family. Such a good man! He said we could stay for free until we got our paperwork in order. Said we could eat the food in his fridge. We were surrounded by so much care. We’re so grateful! He’s an engineer too. He lived in Leipzig and let us use his Dresden apartment. A month and a half later, we got social housing.

Dresden is a wonderful city, but I can’t tell you how awful I felt at first. I wanted to go home, despite the shelling. I felt that the walls of my home would protect me…

Little by little, a year passed. I discovered the Ukrainian House in Dresden. We joined a [Ukrainian] choir called Volia (Freedom). My life is so different now. Oh, and I always look forward to these meetings! We have people from every part of Ukraine here. I always feel so happy when I come here, our women are so wonderful! Clever and talented. We’re all friends now.

We have a coalition of our own! There’s six of us ladies. We can talk to each other about anything, whether it’s politics or love. We each have our own worries, but we help each other through it all. Vlada the therapist is very helpful – she helps us find distractions from our thoughts."

My Grandma Zina, who decided to stay in Ukraine

As I listened to Zina, who had found the courage to leave, I kept thinking about another Zina, my grandma, who found the courage to stay in Odesa.

"I’m not going anywhere," my 93-year-old grandma said in February 2022.

Instead, I went to Odesa, though that wasn’t until May 2023. For a year and a half, I only saw my grandma over Skype.

Every time, she’d ask me to send her a photo of my daughter, her great-granddaughter.

I printed out an entire album of pictures of her, but when I arrived in Odesa, I realised that my grandma had gone almost totally blind.

A phone app interrupted us: "Air-raid warning. Please make your way to a shelter!"

We were lying in bed, under a heavy blanket. I was looking at the green lamp, the cuckoo clock, and the old photos in their frames, and thinking about how much I’d loved being here as a kid.

Grandma always made kotlety (meat patties), pyrizhky (filled yeast-dough pasties), and sweet tea. She was one of the only grown-ups I knew who was never in any rush. We’d play cards or watch TV. While Grandma was doing the dishes or washing the floors – she was always cleaning or tidying up – I’d pull The Man Who Laughs [by Victor Hugo] off the bookshelves and read it out of her sight. For some reason she thought the book was too violent.

"Air-raid warning, air-raid warning."

What should we do?

Move to the hallway? But was it worth it? Grandma would have to sit up, lean on her rollator, and get up.

Should I tell her about the air-raid warning?

She’s hard of hearing. She’s not heard a single explosion yet – she would find out about them from the news or from her friends.

I saw on Telegram that a missile had been launched from the Caspian Sea.

Grandma talked on.

I listened, transfixed. I never knew before that the Murafa Ghetto [in Transnistria] had reached into their apartment, which had housed 30 people instead of the three it was meant for.

The all-clear.

It wasn’t that scary, was it?

It was, actually.

"Grandma, is there anywhere you can see yourself going?" I asked before I left Odesa to travel back to Germany.

I knew there wasn’t. I knew there was nowhere she would go.

She had not left her house for four years.

She is afraid of dying outside, worried that her death would mar someone’s day.

My brother was afraid too.

My parents were afraid too.

But I wasn’t.

I painted her lips red, bought her a wheelchair, and presented her with a fait accompli.

"We’re going to the cemetery."

I asked my brother and my mum’s friend to come along. I wanted her to feel supported.

I knew that she’d want to go on a date with my grandpa, however afraid she was.

Our taxi driver was chatty and kept complimenting Grandma.

"You’re doing well, Grandma," he said. "We’re nearly there now. You’re doing great."

It took us a long time to get there.

It takes a good half an hour to get from the Pryvoz district where Grandma lives to the Tairovske cemetery, with its Jewish corner.

Her cataract prevented Grandma from seeing much, so she kept asking: "Are we really here?"

"Here’s his grave," my brother said.

"I want to be alone with him," Grandma asked.

The sun beat down mercilessly that day.

I put my brother’s hat on Grandma’s head.

The cemetery was empty: only us and the stones.

Jewish people don’t lay flowers on graves.

Flowers wilt and die.

Stones are a symbol of eternity.

As I looked for stones to put on Grandpa’s grave, Grandma was weeping: tears of relief, for her pain had finally found an outlet.

"Ira!" she called out to me.

"Would you like some water?" I asked.

"No! My spot! My spot next to him hasn’t been taken, has it? No one’s bought it, have they?"

Her spot was still free; of course it was.

I realised that Grandma Zina wasn’t going anywhere.

This was her spot, and she had to watch over it, to make sure no one else bought it.

***

War teaches us

that any decision we make is the right one.

War teaches us

that death doesn’t care

about your postal address.

Its letters are always untimely,

even when you’re expecting them.

War teaches us

that it doesn’t matter

whether you go

(leaving your home)

or

stay

(watching everyone who makes that place your home leave).

No one

will have it

easy.

Iryna Fingerova for Ukrainska Pravda

Translation: Olya Loza

Editing: Teresa Pearce