Russia began using chemical weapons back in 2014–2015, says Anton Honchar, Chief Specialist of the Ukrainian Radiation, Chemical and Biological Protection Forces

Kala Kallas, High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, stated in mid-July that Russia is increasing its use of chemical weapons in the war against Ukraine.

Kallas's concern is based on reports from German and Dutch intelligence. Their data shows that since the start of the full-scale invasion, Russia has used chemical weapons at least 9,000 times on Ukrainian territory.

What chemical weapons does Russia most often use in the war against Ukraine? How are cases of the use of chemical weapons recorded? Do the Russians fill Shahed attack UAVs with chemicals?

Ukrainska Pravda put all these questions to Anton Honchar, chief specialist of the Radiation, Chemical and Biological Protection Department of the Armed Forces of Ukraine’s Support Forces Command.

"Even simple vinegar and the smell of onions are, in a sense, dangerous chemicals."

Anton, in the eyes of ordinary Ukrainians, the phrase "chemical weapons" already sounds like a horror story. However, people have little understanding of what this phenomenon is. In simple terms, what are chemical weapons?

First of all, chemical weapons are the means, methods of delivery and storing of toxic substances used in warfare. For instance, mustard gas, sarin, soman, VX, or the more well-known toxic substance Novichok, which was used to poison the Skripal family in Salisbury in 2018.

Chemical weapons themselves are divided into certain subtypes and categories: skin-blistering, nerve-paralysing, etc. In other words, the same substance that has toxic properties and affects the body either wants you to die as quickly as possible or to make you as uncomfortable as possible.

Next are hazardous chemicals, which, in high or low concentrations, regardless of how they are used, can have a negative effect on our bodies. For example, even simple vinegar in high concentrations will have some kind of irritating effect on you. The smell of onions also irritates something in you – the mucous membrane of your eyes, and you feel unwell. This is a dangerous chemical substance.

Therefore chemical weapons are those that are controlled and prohibited by the Chemical Weapons Convention; dangerous chemical substances are those substances that can be used against humans.

When talking about chemical weapons, people first think of World War I, which is often called the "Chemists' War". How have chemical weapons changed over time, and how does the enemy use them?

During World War I, chlorine gas was released by spraying it into the air or by placing barrels which released fumes that drifted with the wind. But then, as now, no one could control the wind. If we were to use chlorine again, everything would depend on the wind – its speed and direction. It's that simple.

Then they began adapting and developing different types of chemical weapons for specific purposes, aiming for maximum effect at minimal cost. As a result, a major issue today is the availability of precursors: substances that can be combined to create chemical weapons.

Sarin, mustard gas and Novichok – these are all chemical weapons prohibited by the Convention, which consists of many articles and has three annexes. These annexes describe all the chemical weapons that are prohibited.

As for the Russian Federation, it has all the necessary capabilities to produce, supply, and conduct research on chemical weapons – and, as we can see, to equip its units with them. In 2018, Russia claimed to the OPCW (Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons) that it had destroyed all its stockpiles.

But given how Russia routinely circumvents laws, regulations, and even basic human norms, there is absolutely no trust in those claims.

The constant universalisation of chemical weapons and their improvement have led all countries to say: wait, this is inhumane, this is not in accordance with international law, this is not in accordance with the norms of warfare.

So, now we see that there is the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, and 193 countries have signed the Chemical Weapons Convention, which, admittedly, not all have ratified. We have ratified it. We are better overall. We do not have chemical weapons and never have. Russia, despite being a signatory to the Chemical Weapons Convention, is directly violating it.

Has Russia ratified the Convention?

Yes. It violates the first article, where point 5 states that dangerous chemicals designed to be used against crowds, also known as riot control agents, cannot be used as a means of warfare.

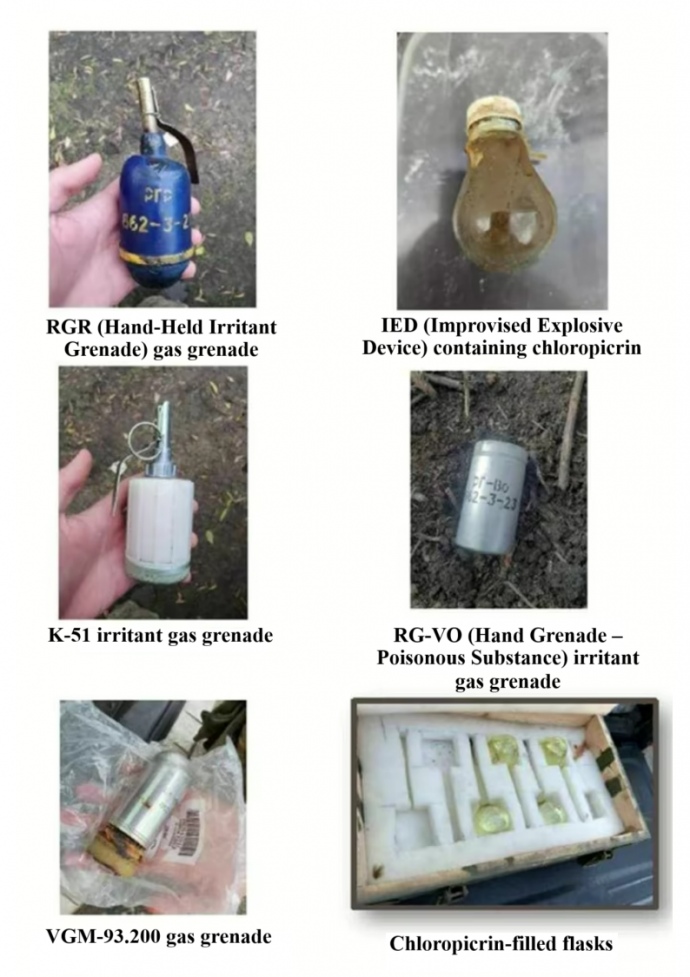

For example, such means as the RG-Vo [Russian-made hand-held chemical grenade – ed.] and K-51 [Soviet hand-held aerosol "tear gas" grenade – ed.] cannot be used as a means of warfare. They can be used to disperse demonstrations, but not as a means of warfare.

Why can they be used to disperse demonstrations?

If there is a crowd, some kind of illegal demonstration that needs to be dispersed, people have the opportunity to leave the area where the dangerous chemical substance is located. They can walk away, wash their eyes and breathe fresh air.

A soldier does not have this opportunity because he is performing the task of defending Ukraine. He cannot just leave the trench or dugout to go out and breathe fresh air, etc. It is impossible. Therefore it is prohibited as a means of warfare.

Why do we hear about some substances often, but not about others? For instance, many people have heard of sarin because it was used in Syria and resulted in severe sanctions, but others that were also used are not mentioned...

Because some substances are much easier to manufacture. There are precursors that are easier to obtain, easier to combine, easier to mix, so to speak, and then we have a substance, for example, with a skin-irritating effect. But in order to create a nerve agent that will directly affect our body, we need much more functionality, many more opportunities for manufacturing and supply.

In other words, there are well-known chemical agents – like the Renaults of the chemical weapons world – and then there are ones like Novichok, which are still not fully understood; you might compare them to a Maybach [German luxury car brand – ed.]. They’re far less common than the chemical weapons already in use because they’re much harder to produce and store.

"It's not what you know that matters, but what you can prove."

You mentioned Novichok, and I immediately thought of the assassination of Stepan Bandera, where poison was used, or the famous "umbrella murder" of Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov in 1978. How often have chemical weapons been used by special services to kill dissidents for political reasons?

There is a film called Law Abiding Citizen. It has a very good line: "It's not what you know, it's what you can prove." The same applies here. We may know about many cases – what happened, where and how – but only what has been proven in a laboratory and in court will count.

Now it is easier to do this, because it is currently possible to detect chemical compounds even remotely. For example, in the case of Mr. Navalny [Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, poisoned with Novichok in Russia and who later died in a Russian prison – ed], the substances were detected remotely. It was found that there was a chemical compound which, according to its spectrometry [a method of determining the structure of a substance – ed.], resembled something that could be a toxic substance used in warfare. Previously, we did not have such new devices or means of detection. Now there are not as many of them as we would like, but at least they exist.

In modern history, for example, the poisoning of former President Viktor Yushchenko is mentioned. Was it chemical warfare?

We have a clear list of chemical weapons and a vague list of hazardous chemicals. Even vinegar, as I said, can be a hazardous chemical, depending on its concentration. In the case of Yushchenko, we can say that it was not a chemical weapon, but a hazardous chemical substance. This is because the substance used against him [dioxin – ed.] is not listed by the OPCW.

"Russia started using chemical weapons in 2014-2015"

Let's move on to the Russian-Ukrainian war. Why is it that we mostly learn about the use of chemical weapons from Western intelligence reports? Do we have any statistics of our own?

We have Support Forces Command, where I come from, and we have mobile sampling teams. These are specialised groups that are very mobile, fast, equipped with the latest facilities, and they take these samples, let's call it that, together with the Security Service of Ukraine or the Special Operations Forces. These are the people who take samples of hazardous chemicals, grenades, munitions, clothing, filter boxes on gas masks, etc. on the contact line.

More than 10,000 cases of the use of hazardous chemicals on the battlefield have been recorded since February 2023. Yesterday there were 7 cases, and over the previous month, there were 760 cases.

And why from February 2023?

Until then, we didn't have the capacity to properly organise the sampling process. The Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons has something called a "chain of custody" for legal accountability. If anything is done incorrectly or any procedure is violated, the evidence cannot be presented in court as admissible proof.

Our services are handling all of this brilliantly - once again, huge thanks to them. They're not only initiating criminal proceedings here in Ukraine, but also working through the International Court of Justice via the OPCW. They issue a report stating, for example, that a specific type of grenade was used against Ukrainian units on the line of contact - a grenade that violates Article 1, paragraph 5 of the Chemical Weapons Convention, which both Russia and Ukraine have signed. So, who’s to blame? Exactly - we point the finger at them [the Russians – ed.]. The Armed Forces of Ukraine have never used such weapons, whereas the Russians use them constantly.

In fact, the Russians started using chemical weapons in 2014-2015, but we just didn't have any mechanisms to record it.

And how does this happen directly on the front line? I find it hard to imagine how you can, for example, arrive at the front line and take something away. How do you gain access there?

That's the most interesting part. Our mobile sampling teams, together with the Security Service of Ukraine’s soldiers, are fully trained to operate both day and night. We’ve got electronic warfare systems - everything is as well-equipped as possible. You have to understand: when you're heading there, it's 100% certain they'll be waiting for you. The teams go in, collect the samples quickly - everyone already knows exactly what they’re responsible for: where to park the vehicle, what to do, who to speak to, what to collect, and so on.

When are chemical weapons most often used? On which fronts are they most prevalent and which enemy units are most likely to use them?

On fronts where they need to push out our defenders, where, roughly speaking, according to Russian theory, they need to drive them out. Chemical grenades are most effective during the warmest part of the day, when evaporation is at its maximum. That is, in summer, spring, and autumn. Winter is not so good, as it dampens the effect.

Next is day or night. Here it's a 50-50 question. They use them in roughly the same correlation, only a little more during the day, because they are conducting active assaults and, accordingly, they use hazardous chemicals for them.

The largest percentage of assaults is, of course, on the Pokrovsk front, and on Kupiansk, Lyman and others.

Recent reports constantly mention a substance called chloropicrin. Is this the most common substance used by the Russians?

Chloropicrin was previously used to test gas masks. That is, a tent was erected, service personnel put on gas masks, chloropicrin was dripped into the tent and it evaporated. If the gas mask was fitted correctly, you would not feel anything and could leave the tent. If the gas mask was poorly fitted or the filter box did not filter properly, you would start to cough, your eyes would water, etc. This is a Soviet practice. Russia has a lot of chloropicrin in stock specifically for fumigation, and they use it.

Is chloropicrin mostly found only in grenades or some kind of artillery shells? In other words, do they fill anything else besides grenades with chemicals?

In 88% of cases, various types of grenades are used: RG-Vo, K-51, etc. The rest are artillery shells, and even fewer cases involve simple aerosols that can be sprayed somewhere – because these are close-contact battles, anything is possible.

In second place in terms of usage are improvised devices. Simply put, they take a lightbulb, fill it with chloropicrin or some kind of liquid, and drop it from a drone. It’s difficult to collect a sample from such a device because, as you can imagine, the substance will be scattered across the area. But our mobile teams are managing to do it.

Are thermobaric weapons classified as chemical weapons?

No. Thermobaric weapons are also not classified as chemical weapons. They have a completely different effect – they create excess pressure. They have proven themselves perfectly, just like infantry jet flamethrowers and thermobaric grenades dropped from drones. We have a whole range of them, as well as mobile jet flamethrower systems called Sivalka.

Let's move on to debunking myths. Can the Russians put some kind of chemical substance in the Shahed [drone – ed.] to spray something when it flies into a residential area?

What's the point? If the Shahed is flying to explode, what's the point of putting anything in it? It all depends on the conditions in which the chemical substance ends up. If there is a strong wind and the air temperature is high, then literally within half an hour, there will be nothing left. This is not true, I want to say right away: don't be fooled by fake news. This is disinformation from the Russian Federation.

Do you know who supplies chemical weapons to Russian units? Are there any special units in the Russian army that make something like radiation, biological or chemical weapons?

Yes, there are research laboratories that manufacture them. As for those who supply them to the units, I would like to mention a case from last year. They had a commander of the RCB [radiation and chemical warfare – UP] forces, General Kirillov. On 16 December 2024, the Security Service of Ukraine served him with a notice of suspicion, and on 17 December, he was killed when his scooter exploded. This was very effective because he directly gave orders regarding the distribution and provision of these grenades to the frontline units on the line of contact and gave instructions.

Is there a unit of the Russian army that is most noted for its use of chemical weapons?

The 155th Marine Brigade, and others.

In conclusion, let's try to talk about what chemical, biological and radiation protection looks like and what to do. When to be afraid, when to panic, and when not to do any of that.

The most important thing is that if you have certain knowledge, skills and abilities, then you are no longer afraid, you already know. Fear is lessened.

Next is protective equipment. Never leave your protective equipment anywhere; always keep it with you. This includes gas masks, respirators, goggles and filter boxes.

Next comes all the hazardous chemicals we are considering, or chemical weapons, are not exactly gases, they are liquids. Yes, they are volatile, but they are liquids. Always stay away from unfamiliar liquids or strong odours. If you smell a strong odour, please call our experts, and we will help you.

And finally, don't be fooled by fake news, always check information and trust only official sources.

Author: Yevhen Buderatskyi, UP

Translation: Myroslava Zavadska and Yelyzaveta Khodatska

Editing: Susan McDonald